No, don’t worry, I am not declining a job, refusing a honor, or rejecting a contract. It’s just chess.

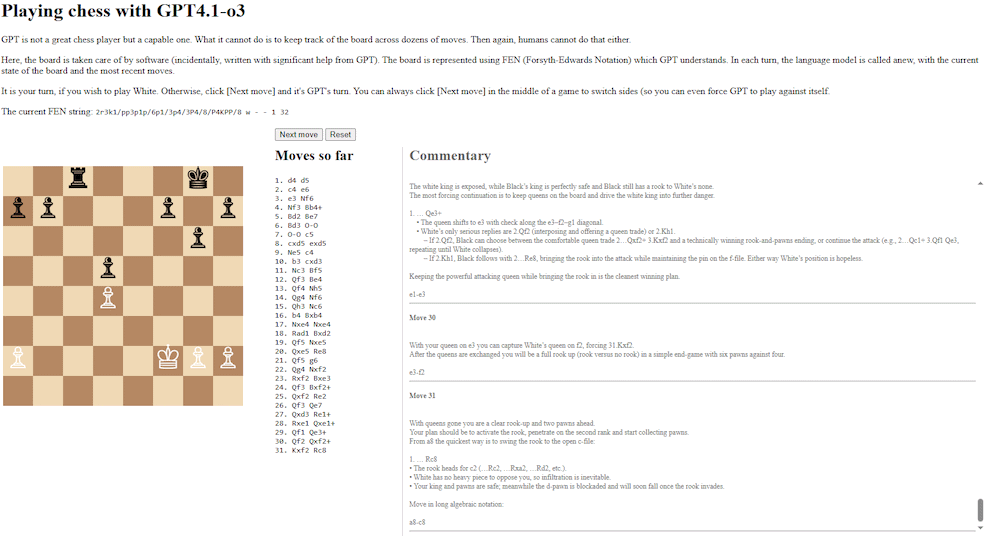

GPT, specifically the GPT4.1-o3 model, just beat me in chess. I was playing white. GPT won in 31 moves.

The fact that I am beaten in a game of chess by even a minimally capable opponent should come as no surprise. I can “play” in the sense that I am aware of the rules and the basic strategy; but I cannot really “play” in that I have near zero actual chess playing experience, having played my last recreational chess game decades ago. I appreciate the game’s elegance but somehow, I never acquired the taste.

Still, I felt compelled to build this user interface and run these tests, to appreciate just how well (or how badly) a frontier-class AI model can play chess. Especially in light of all that recent nonsense about how a nearly half-century old Atari 2600 with a chess cartridge managed to beat GPT.

It didn’t, really. What that experiment proved is simply that GPT is not capable of tracking the state of a board internally across multiple conversational turns. So what? Neither can humans.

But once you give GPT a board, it all changes. That’s exactly what I did: I encoded the board as a FEN string and in each conversation, presented GPT with the board along with the two most recent moves, and ask the model to make a move. When you look at this game we played… GPT beat me fair and square. Again, I am not exactly hard to beat in chess, but still.

The board was needed also because it enforced the rules. At one point (move 15 below), GPT misplaced in its “mind” one of its bishops and tried to make an illegal move. The board rejected the move and GPT was asked to provide another move, which it did.

GPT was also asked to analyze the board at each turn, an analysis that took shape in the form of a running commentary, which I reproduce in its entirety below.

Move 1

White has opened with 1.d4, staking a pawn in the centre and freeing the c1-bishop.

As Black you have the usual range of sound replies:

• 1…Nf6 – heading for a King’s Indian, Grünfeld or Nimzo/Queen’s Indian setup later.

• 1…e6 – keeping everything flexible and eyeing …d5 or a possible French structure.

• 1…c5 – an immediate Benoni/Benoni-like strike, though it gives White the option of 2.d5.

• 1…g6 – the Modern/King’s Fianchetto.

• 1…c6 – the Slav/Caro-Slav move, preparing …d5 under excellent conditions.

• 1…d5 – the most straightforward, fighting for the same central square and keeping maximum piece freedom.

Among these, 1…d5 is the simplest, developing none of your pieces yet but contesting the centre immediately and avoiding any commitment of your king-side structure. It also keeps the opening lines mainstream (Queen’s Gambit Declined paths, Slav-type positions, or the exchange line after 2.c4 dxc4).

Therefore, I choose the solid central response.

d7-d5

Move 2

After White’s 2 .c4 the position is the classical Queen’s Gambit: your pawn on d5 is supported, the c-pawn is putting pressure on the centre, and both sides still have all pieces undeveloped.

Typical replies for Black are:

1. Accept the gambit with 2…d5xc4 (Queen’s Gambit Accepted).

2. Decline with 2…e7-e6 (Queen’s Gambit Declined) or 2…c7-c6 (Slav Defence).

Accepting immediately gives up the centre for the moment and hands White a tempo or two for development; declining with …e6 keeps the strong pawn on d5 and prepares …Ng8-f6 and …Bf8-e7 (or …Bb4) while leaving all options open for castling and later central breaks with …c5 or …e5.

Choosing the solid Queen’s Gambit Declined setup, the most natural move is 2…e6.

e7-e6

Move 3

The position is a typical Queen’s Gambit Declined structure.

White has advanced the c- and d-pawns, and with 3.e3 intends to consolidate the centre and develop the king-side pieces calmly.

Black stands solid: the d5- and e6-pawns form the usual QGD pawn chain, and all pieces are on their original squares, ready to develop.

Strategic considerations for Black:

1. Rapid development and king safety: getting minor pieces out and castling are top priorities.

2. Pressure on the d4-pawn: once the king knight reaches f6, Black can support …c5 or …e5 breaks later, or put a bishop on e7 or b4.

3. Flexibility: keeping options open for either …c5 (Tarrasch-like) or …c6 (Semi-Slav / Orthodox) structures.

The natural, principled move that addresses all three points is to develop the king knight:

• The knight on f6 attacks d5 and helps control e4.

• It prepares quick castling.

• It leaves both …c5 and …c6 possibilities available for the next few moves.

Therefore, I play:

g8-f6

Move 4

The position is a Queen’s Gambit Declined structure where both sides have developed knights and laid claim to the centre with the d- and c-pawns.

As Black you have several normal developing possibilities:

1. …Be7 – the classical Queen’s Gambit route.

2. …c5 – directly striking at the centre (Tarrasch/IQP structures).

3. …Nbd7 – quiet development.

4. …Bb4+ – an active check that develops a piece, forces White to reveal how he will block, and often induces Nc3, giving Black typical Nimzo-style play.

Because …Bb4+ develops with tempo, keeps castling next and does not concede anything in the centre, it is an attractive choice here.

Black plays

f8-b4

Move 5

Your bishop on b4 is en prise: if it stays where it is, White can simply play Bxb4 next move.

Rather than exchanging it for the bishop on d2 (which would give away your active dark-squared bishop), you can keep the bishop and maintain the pressure by retreating along the long diagonal.

The safest square that continues development and prepares quick castling is e7.

Move (long algebraic):

b4-e7

Move 6

The position is a fairly typical Queen’s Gambit Declined structure, but with White’s dark-squared bishop already committed to d3 and the light-squared bishop on d2. Black’s development is solid; the only pieces still at home are the queen-side knight and the c8-bishop. White has the customary space advantage on the queen side (pawns on c4 and d4) and will probably continue with Nc3 followed by 0-0 and perhaps Rc1, aiming for pressure along the c-file or a possible minority attack (b4–b5 later).

Black’s main strategic tasks:

1. Finish development quickly (…0-0, …Nbd7, …c5 or …dxc4 followed by …c5).

2. Challenge White’s central pawns before they can advance.

3. Keep an eye on the h7-square: after we castle, White’s bishop on d3 does hit h7, but without a knight on g5 the classical Bxh7+ sacrifice is unsound.

Among the candidate moves:

• 6…c5 immediately is perfectly playable and leads to known lines after 7.cxd5 Nxd5 or 7.0-0 0-0, but it leaves the king in the centre for another move.

• 6…dxc4 7.Bxc4 0-0 is also fine, but it voluntarily releases central tension and lets White’s bishop sit actively on c4.

• 6…Nbd7 is solid but a bit passive; we will still have to castle and only then decide on …c5 or …dxc4.

The safest, most flexible move is simply to castle first. It completes development, connects the rooks and carries no tactical risk—there is no sound Bxh7+ sacrifice here because …Nxh7 is always available.

Therefore I choose to castle kingside.

e8-g8

Move 7

The position is a typical Queen’s-Gambit-style structure:

• White controls the centre with pawns on d4 and c4, pieces developed to d3, d2 and f3, and has just castled.

• Black is solid but slightly cramped; the light-squared bishop on c8 and the queen-side knight still need to get into play.

• The only immediate tactical idea for White is the classic Bxh7+ sacrifice. With the knight already on f3 that idea requires 8.Bxh7+ Kxh7 9.Ng5+, but after …Kg8 the attack is insufficient. Still, it is prudent for Black not to make weakening pawn moves such as …h6 or …g6 right now.

Strategically, Black wants to:

1. Challenge White’s centre.

2. Free the c8 bishop and the b8 knight.

3. Keep the king safe and avoid giving White an easy target on the kingside.

The natural way to achieve all three aims is the classical break …c7-c5.

• It immediately attacks White’s d4-pawn and prepares either …dxc4 or …exd5, depending on White’s reply.

• After …c5 the c8 bishop will often come out to b7 or g4, and the b8 knight gets the c6 square.

• The move does not create new weaknesses around the Black king.

Hence the best continuation is:

c7-c5

Move 8

After 8.cxd5 White’s pawn from c4 has captured on d5.

Recapturing with the e-pawn restores material equality, places a Black pawn on the strong central square d5, and opens the diagonal for the c8-bishop.

e6xd5

Move 9

The position comes from a typical French-Tarrasch structure.

White’s knight on e5 is annoyingly centralized and the bishop on d3 controls the important h7–b1 diagonal.

Black would like to:

1. Drive the d3-bishop off that diagonal.

2. Gain space on the queenside.

3. Prepare …Nc6 to challenge the e5-knight under better circumstances.

Pushing the c-pawn fulfils all three aims:

• After 9…c5-c4 the bishop on d3 is attacked and must move, giving Black a valuable tempo.

• The advance fixes the d4-pawn and clamps the light squares (b3, d3).

• Once the bishop retreats, …Nb8-c6 (or …Nb8-d7) can follow, directly contesting the knight on e5.

Tactical check:

If White tries 10.Nxc4? then 10…d5xc4 wins a piece; after 11.Bd3xc4 Black is a full minor piece up for two pawns.

Therefore White’s best is simply to move the bishop (10.Bc2 or 10.Be2), after which Black continues with …Nc6, equalising and even taking the initiative.

Hence the immediate pawn thrust is both safe and strong.

c5-c4

Move 10

The pawn on c4 can capture the white bishop on d3, eliminating one of White’s most active pieces and gaining material. After

10… c4xd3

Black will have exchanged a pawn for a bishop and will stand two points ahead. White’s most plausible reply is 11.Nxd3, after which Black can continue with …Bf5 or …Nc6, pressuring the knight and consolidating the extra material.

c4xd3

Move 11

Your advanced pawn on d3 is the spear-head of Black’s initiative.

By exchanging it for White’s c-pawn you

• eliminate White’s last central pawn besides d4,

• remove an important defender of the d4–square,

• open the d-file for your queen and rooks,

• and leave yourself a healthy extra minor piece with no structural weaknesses.

After 11…d3xc2 12.Qxc2 you can follow up with …c7-c5, attacking d4 and rapidly mobilising your queenside majority; Black’s pieces will come out smoothly (…Nb8-c6, …Bf5 or …Bd6, …Rc8), and the extra piece should decide.

d3xc2

Move 11

The pawn on d3 is a valuable spearhead in Black’s position.

Developing the queenside bishop to f5 both

• reinforces the pawn on d3,

• places the bishop on an active diagonal (b1–h7),

• prepares …Rc8 or …Nc6, and

• sets tactical ideas such as …Nxg4 if White answers with g2-g4.

After 11…Bf5, typical continuations are:

A) 12.g4 Nxg4 13.Nxg4 Bxg4, leaving Black a healthy extra pawn.

B) 12.f3 h6 (or 12…Nc6), keeping the strong outpost on d3.

C) 12.Qf3 Be4, forcing White’s queen off the diagonal and keeping up the pressure.

No immediate drawbacks are apparent for Black, whereas passive moves would allow White to eliminate the d3-pawn with Nxe3-d3.

Therefore the most natural and sound continuation is:

c8-f5

Move 12

The bishop on f5 is currently hanging: White is threatening 13 .Qxf5, winning the piece.

By retreating the bishop we not only remove it from capture but turn it into an active, tactical weapon.

12…Bf5–e4 (Be4)

• The bishop steps to a secure square and immediately attacks the White queen on f3.

• It also points along the long diagonal toward g2 and h1, creating latent pressure on the White king-side.

• If 13.Nxe4 dxe4 the bishop/knight exchange leaves Black with a powerful supported pawn on e4 that again attacks the White queen; White cannot reply 14.Qxe4 because 14…Nxe4 wins the queen.

• Any queen retreat such as 13.Qg3 or 13.Qe2 leaves the pawn on d3 firmly anchored and the e4-bishop dominating the position, after which Black can continue with …Nbd7, …Rc8 or …Bb4, steadily improving.

The move eliminates the immediate tactical problem and seizes the initiative.

f5-e4

Move 13

The bishop on e4 is a central monster, tying down White’s kingside and supporting the advanced pawn on d3.

White’s last move 13.Qf4 attacked this bishop, but it also left the queen slightly exposed.

By moving our knight with tempo we:

• Attack the white queen.

• Remove the only defender of the e4-square (the queen); if White captures 14.Qxe4 we reply 14…dxe4 winning the queen.

• Keep all our active pieces on the board and maintain control of the dark squares.

The only safe retreat square for White’s queen after our move is g4; everywhere else it is captured.

Best is therefore the forcing:

f6-h5

Move 14

The key feature of the current position is Black’s strong dark-squared bishop on e4 and the advanced passed pawn on d3, while White’s queen on g4 is exposed.

Your knight on h5 is doing nothing constructive; by repositioning it to f6 you:

1. Attack the White queen on g4, forcing her to move.

2. Bring the knight back toward the centre, where it helps protect the king and supports the bishop on e4.

3. Keep firm control of g4, e4 and d5, and prepare …d4 or …c5 in the future while preserving the extra pawn on d3.

Other tempting moves such as 14…f5? would allow 15.Qxh5, losing a full knight, so the safe and strong regrouping move 14…Nf6 is preferable.

Move:

h5-f6

Move 15

Your queen on h3 lies directly on the long diagonal of my dark-squared bishop on d7.

There are no pieces between them (e6, f5 and g4 are empty), so I can simply capture the queen, winning decisive material.

After 15…Bxh3 the only plausible reply is 16.gxh3, when Black is a full queen up and can continue with moves like 16…dxe4 or 16…Nc6 with an overwhelming position.

d7-h3

Move 15

After assessing the position, the safest and strongest continuation is to complete the development of the queenside knight while reinforcing the pressure on d4 and e5 and preparing …Bxd3 if White grabs the pawn on d3.

My move:

b8-c6

Move 16

The pawn on b4 is hanging and there are no tactical drawbacks to removing it immediately.

After 16…Bxb4

1. The bishop arrives on an excellent diagonal (b4-e1) and at the same time wins a pawn.

2. If White plays 17.Rab1 we can answer 17…Bxc3, eliminating one of the knights and keeping the extra pawn.

3. If 17.Nxc6 bxc6 18.Nxe4 dxe4 we again stay a pawn up, while the passed pawn on d3 (now e4) and the c6-pawn give Black lasting pressure.

Other tries such as 17.Nxe4 Nxe4 18.Bxb4 Nxb4 leave material equal but with Black’s outside pawn majority and advanced d3-pawn offering the better chances.

In short, 16…Bxb4 is safe, wins material at once and keeps the initiative.

e7-b4

Move 17

After evaluating the possibilities, the strongest continuation is to eliminate White’s central knight immediately, keeping your minor-piece majority and preserving your advanced pawn on d3.

The resulting positions favor Black in every major line (18.Bxb4, 18.Nxc6, 18.Nxd3 or 18.f3), leaving Black at least one extra minor piece with no compensation for White.

Move:

f6-e4

Move 18

Black is already a full minor-piece up and has an advanced passed pawn on d3.

White’s last move (Rad1) lined the rook up with the bishop on d2, hoping to recapture on e4 or d3 and untangle.

We can exploit the overload of that rook/bishop tandem:

1. Our dark-squared bishop on b4 captures the white bishop on d2.

• If White recaptures with 19.Rxd2, our knight on e4 jumps to d2, winning the rook (19…Nxd2) and leaving us a rook and a piece ahead.

• If White instead tries 19.Nxc6, we simply reply 19…bxc6 and remain a clear piece up while the bishop on d2 still attacks the rook on f1.

Either way, 18…Bxd2 is the cleanest and most forcing continuation.

b4-d2

Move 19

The key tactical problem in the position is the double attack on the f7–pawn by White’s queen on f5 and knight on e5.

By eliminating the white knight we remove one of the attackers, simplify the position, and keep our large material advantage (we remain two minor pieces up).

1. … Nxe5

After the knight capture:

• If 20.dxe5, the queen remains exposed to …g6 (hitting the queen and shutting the f5-h7 diagonal) and Black keeps an extra knight and bishop.

• If 20.Qxe5, 20…Re8 drives the queen away and Black still has an extra bishop and knight.

In every continuation Black is safely ahead.

c6-e5

Move 20

Black is ahead a piece but the knight on e4 is presently attacked by White’s queen.

Moving the rook to e8 simultaneously:

• removes the rook from the pin on the f-file,

• attacks the white queen, forcing it off the e-file, and

• tactically protects the knight on e4 (if 21.Qxe4, then 21…Rxe4 wins White’s queen).

This keeps the extra material and maintains control of the position.

f8-e8

Move 21

After 21.Qf5 White’s queen is very active but also rather short of safe squares and, crucially, it sits directly in front of your f-pawn.

Your minor pieces are excellently posted (bishop d2 and knight e4) and the protected passed pawn on d3 gnaws away at White’s centre.

The simplest and most forcing way to capitalise is to drive the white queen off the f-file. Pushing the g-pawn does just that:

1. … g7-g6

• The pawn on g6 attacks the queen on f5; she must move.

• If 22.Qxf7+? the black king calmly plays 22…Kxf7 and wins the white queen on the spot – Black keeps his own queen and emerges a full queen and minor piece up.

• If 22.Qxe4, 22…d5xe4 again picks up the queen.

• Retreats such as 22.Qf4 or 22.Qh3 leave Black with a huge material advantage (still up two minor pieces), a strong passed pawn on d3 and the better prospects on every sector of the board.

There are more elaborate winning lines, but 1…g6 is the most direct and completely safe.

g7-g6

Move 22

The position is overwhelmingly in Black’s favour:

• Material – Black has an extra bishop and knight.

• Piece activity – Black’s minor pieces (B d2 and N e4) are powerfully posted; the knight on e4 attacks c3, d2, f2, g3, g5 and, crucially, the white queen.

• King safety – the black king is perfectly safe behind the g6-pawn, while the white king is short of defenders.

Tactical motif: the white pawn on f2 is the only defender of g3/h2 squares and also shields the white king from the black pieces. Removing that pawn with the knight comes with tempo (it attacks the queen and the rook on d1) and wins material.

Calculation:

1. … Nxf2

If 2. Rxf2 Bxe3+ wins another pawn and keeps a clear extra bishop.

If 2. Qf3 (or Qe2 / Qf4) Nxd1 snatches a whole rook; after 3.Qxd1 Black is up a full rook for a knight (still a bishop ahead overall).

There are no lines in which White can avoid heavy material loss; therefore this is the most direct and strongest continuation.

e4-f2

Move 23

Your minor-piece on d2 is perfectly placed: it both restrains White’s centre and eyes the weak e3–pawn that shields the White rooks.

By playing …Bxe3 you

• remove the last pawn that guards the rooks on the f- and d-files,

• attack the f2–rook directly,

• open the d-file for your queen and rook, and

• keep the option …Bxf2+ in many follow-ups, winning material outright if the rook on f2 is not evacuated.

No immediate counter-tactic for White works:

• 24.Qf3? Bxf2+ wins the exchange.

• 24.Rxd3 Bxf2+ also wins the exchange.

• 24.Rf1 Re4 (or …Qe7) leaves Black a healthy extra piece and a dominating position.

So the cleanest continuation is simply to take on e3 now.

d2-e3

Move 24

Your bishop on e3 has both tactical and strategic power:

• It pins the white rook on f2 to the king on g1.

• It already attacks the pawn on d4 and supports your central passer on d3.

• The rook on e8 stands behind it on the open e-file, ready to invade.

By moving the bishop one step along its long diagonal you win material immediately while exposing the white king.

The main line is:

24… Bxf2+ 25.Qxf2 Re2!

If White takes the rook (26.Qxe2) the pawn d3–e2 wins the white queen and promotes; if White instead tries 26.Qxf7+ Kh8, you remain a full rook and two pawns up with a crushing position.

Hence the immediate capture is the strongest continuation.

e3-f2

Move 25

Black is a clear rook and three pawns up and has a dangerous passed pawn on d3.

The most direct way to exploit the material advantage is to drive the white queen off the second rank (or win it outright) while invading with the rooks.

1. … Re2! does exactly this:

• The rook on e8 lands on e2 with tempo, attacking the white queen on f2.

• If 26.Qxe2, then 26…dxe2 wins the white queen and leaves Black a queen + rook versus a lone rook.

• If 26.Qf3 (or 26.Qf1), Black keeps the rook on the second rank, eyes g2 and h2, can pick up the a-pawn with …Rxa2, and can follow up with …Qe7 or …Qe8 to prepare …Re1+.

• If 26.Rxd3, Black replies 26…Rxf2+, again removing the white queen and keeping a huge material edge.

After …Re2 Black is winning by force in every line.

Therefore the best move is:

e8-e2

Move 26

The immediate tactical problem we must neutralise is White’s threat of 27.Qxf7+ which would check the king and pick up material.

By transferring our queen to the e-file we guard the f7-pawn, keep the e-file under our control and prepare ideas such as …Re1+ should White capture the d3-pawn.

1. … Qe7 fulfils all of these aims:

• Protects f7, eliminating the check on f7.

• Keeps the d3-pawn protected (queen now also covers it).

• Sets up the sequence 27.Qxd3 Re3 28.Qxe3 Qxe3+ winning a queen, or

27.Rxd3 Re1+ 28.Rxe1 Qxe1+ winning a rook.

• Maintains a decisive material advantage in every line.

Therefore the most solid and forceful continuation is:

d8-e7

Move 27

Your rook on e2 is under attack from White’s queen on d3, but this also allows a decisive invasion on the back rank.

1. … e2-e1+

The rook drops to e1 with check:

• If 2.Rxe1 Qxe1+ 3.Qf1 (only move) Qe3+ (or exchange queens) and Black remains a full rook up.

• If 2.Kf2 (or 2.Qf1) Black plays 2…Rxd1 (or 2…Rxf1+) followed by …Ra8-e8, again leaving Black a rook (or a queen) up with a won position.

Whichever defence White chooses, Black converts the extra material easily.

e2-e1+

Move 28

Your rook sacrifice accomplished its purpose: the white monarch is fixed on the back rank and the only remaining major piece protecting him is the queen on d3.

Now the simplest and strongest continuation is to take the rook on e1 with check.

After 28…Qxe1+ the line 29.Qf1 Qxf1+ 30.Kxf1 leaves Black a full rook and three pawns up in a rook-versus-bare-king ending, which is completely winning.

If White declines the queen trade (for example with 29.Qf1 Qe3+), further checks drive the king into the open while Black keeps the extra rook and pawns.

e7-e1+

Move 29

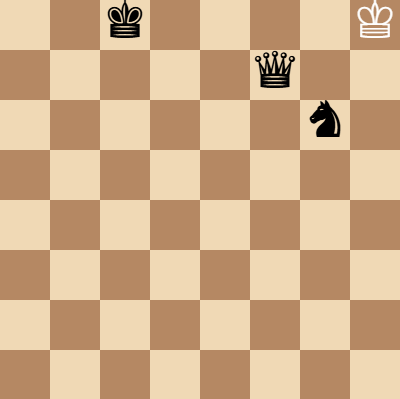

Material balance and king safety strongly favor Black:

Black pieces

• King: g8

• Queen: e1

• Rook: a8

• Pawns: a7 b7 d5 f7 g6 h7

White pieces

• King: g1

• Queen: f1

• Pawns: a2 d4 g2 h2

The white king is exposed, while Black’s king is perfectly safe and Black still has a rook to White’s none.

The most forcing continuation is to keep queens on the board and drive the white king into further danger.

1. … Qe3+

• The queen shifts to e3 with check along the e3–f2–g1 diagonal.

• White’s only serious replies are 2.Qf2 (interposing and offering a queen trade) or 2.Kh1.

– If 2.Qf2, Black can choose between the comfortable queen trade 2…Qxf2+ 3.Kxf2 and a technically winning rook-and-pawns ending, or continue the attack (e.g., 2…Qc1+ 3.Qf1 Qe3, repeating until White collapses).

– If 2.Kh1, Black follows with 2…Re8, bringing the rook into the attack while maintaining the pin on the f-file. Either way White’s position is hopeless.

Keeping the powerful attacking queen while bringing the rook in is the cleanest winning plan.

e1-e3

Move 30

With your queen on e3 you can capture White’s queen on f2, forcing 31.Kxf2.

After the queens are exchanged you will be a full rook up (rook versus no rook) in a simple end-game with six pawns against four.

e3-f2

Move 31

With queens gone you are a clear rook-up and two pawns ahead.

Your plan should be to activate the rook, penetrate on the second rank and start collecting pawns.

From a8 the quickest way is to swing the rook to the open c-file:

1. … Rc8

• The rook heads for c2 (…Rc2, …Rxa2, …Rd2, etc.).

• White has no heavy piece to oppose you, so infiltration is inevitable.

• Your king and pawns are safe; meanwhile the d-pawn is blockaded and will soon fall once the rook invades.

Move in long algebraic notation:

a8-c8

With Black up by a rook and two pawns, I had no chances. I resigned.

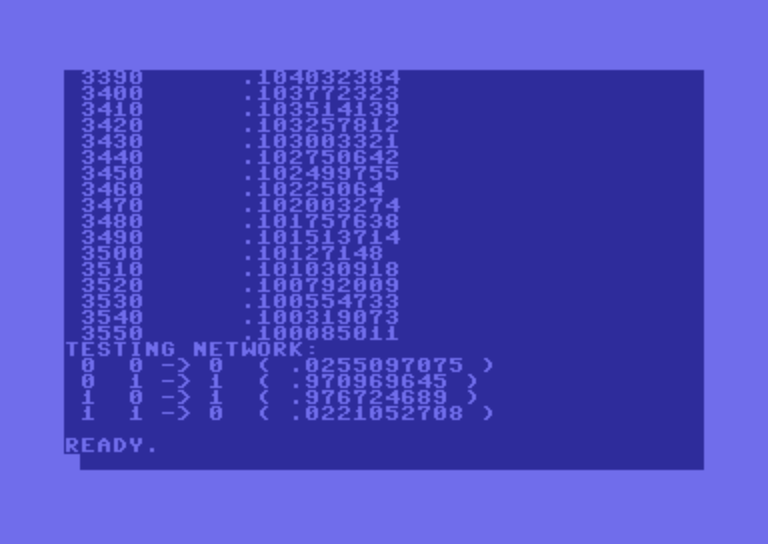

Lesser models, even GPT4.1, are not quite this capable. It appears that the “reasoning” capability of GPT4.1-o3 plays a non-trivial role in its ability to coherently analyze the board.