It’s done.

I changed my primary workstation from Windows 10 to Debian with KDE. Hello, world, please say hello to my nice new KDE desktop.

I am really one of the least likely candidates to make this switch. I have been using Windows as my primary desktop operating system since Windows 3.0, back in 1990. That is a long time. And although I’ve been using Linux for almost as long (1992, SLS Linux 0.96pl12), I never quite made the switch to a Linux desktop.

I came the closest in 2001. That’s when Microsoft introduced Windows XP, with Activation. I despised Activation. This was the first time Microsoft made you feel like your computer is not yours anymore, you’re just rending space from Microsoft. So I went in almost all the way. Slackware Linux with KDE. A nice desktop. I even managed to get my essential Windows applications running (with minor glitches.)

However, I was able to secure instead a small business volume license (which at the time did not require Activation). Not to mention that there was just too much friction. My primary client base was using Windows. I was developing for Windows. Heck, I even wrote books on Visual C++. So I stayed with Windows.

I “survived” Vista by ignoring it. Windows 7 was decent. Once again I “survived” Windows 8, and I eased myself into Windows 10 after discovering third-party apps that allowed me to keep a working Start menu (instead of that abomination Microsoft introduced after trying to get rid of the Start menu altogether) and allowed me to keep my desktop widgets that I got so used to.

Windows 10 at first was touted as Microsoft’s “forever” operating system, with no pre-announced sunset date. Sadly, that changed. Eventually, Microsoft did decide to retire Windows 10 in favor of its successor, Windows 11.

And now comes the saddest part. I was ready to upgrade. Not necessarily eager, especially now with everything that I knew about Windows 11 but hey, you have to move with the times and all.

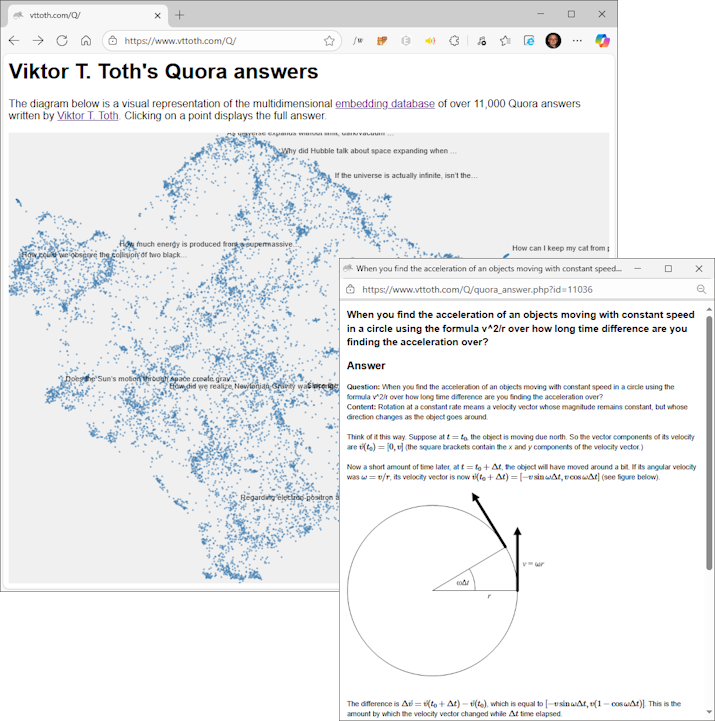

Except… Except that Microsoft made it impossible. You see, my hardware is not young. Between 1992 and 2016, it appears that I replaced my hardware more or less like clockwork, every 6 years or so. And I had every expectations to continue doing that, say, in 2022… except that there was no point. The hardware I would have built in 2022, or for that matter even now, in early 2026, would be virtually identical to my 10-year old boxes, with only marginal gains. A decent (but low power, for longevity/low thermal load) Xeon CPU, 32 GB ECC RAM, a good quality motherboard, a better PSU. What qualified as a robust, solid workstation in 2016, it turns out, continues to qualify as a robust, solid workstation in 2026. Moore’s law appears to be dead. One notable exception may be the GPU and indeed, my new-old workstation has a fairly new GPU (for CUDA/machine learning work), but for that, I do not need to ditch the old hardware. Hardware that still works reliably. Hardware, of which I have redundant backup. Yet Microsoft would want me to turn all that into e-waste because… because my perfectly decent 4th generation Xeons are a teeny bit older than what Microsoft deems acceptable, and the motherboard does not support TPM 2.0, which I do not want anyway. (Contrary to suggestions, the trusted platform module is not about you trusting your computer; it’s about the likes of Microsoft trusting that they can control your computer.)

So Windows 11 was out. But… what about Windows 10 extended support? And that’s where the story turns surreal. You see, I have some very legitimate licenses of Windows, on account of the fact that for many years, I’ve been a Visual Studio Enterprise subscriber. In fact, my subscription goes back to the early beta days when it was called the Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN.) Under this license, I have legitimate copies of everything, including all versions of Windows, with appropriate activation keys. Except… except that these licenses do not entitle me to extended support. Worse yet, I cannot even buy extended support. The version of Windows 10 I installed foolishly back in 2016 is Windows 10 Enterprise. Yes, you can get extended support for Windows 10 Enterprise… assuming you acquired it as a business, through a volume license. Which I didn’t.

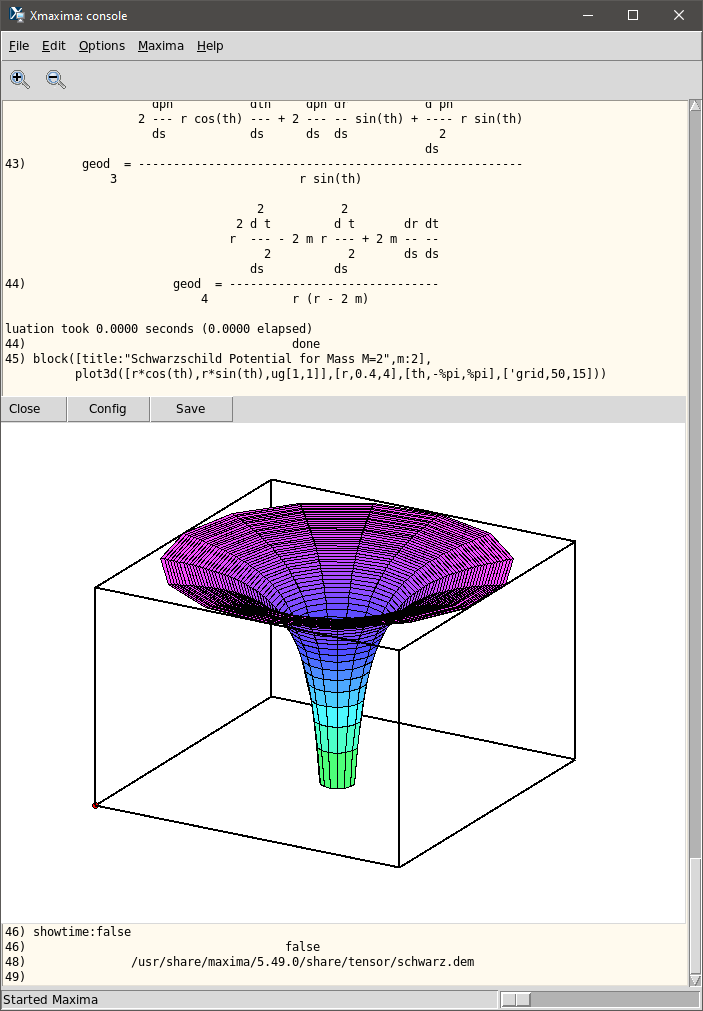

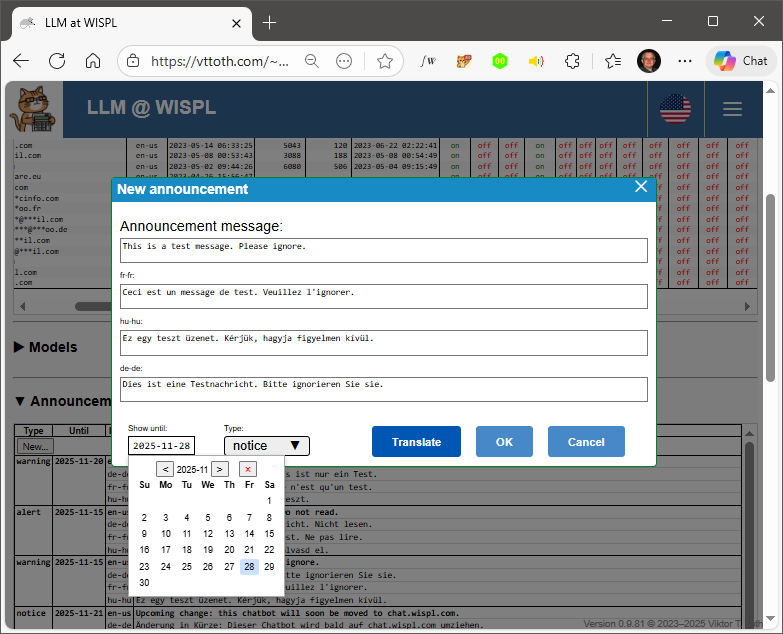

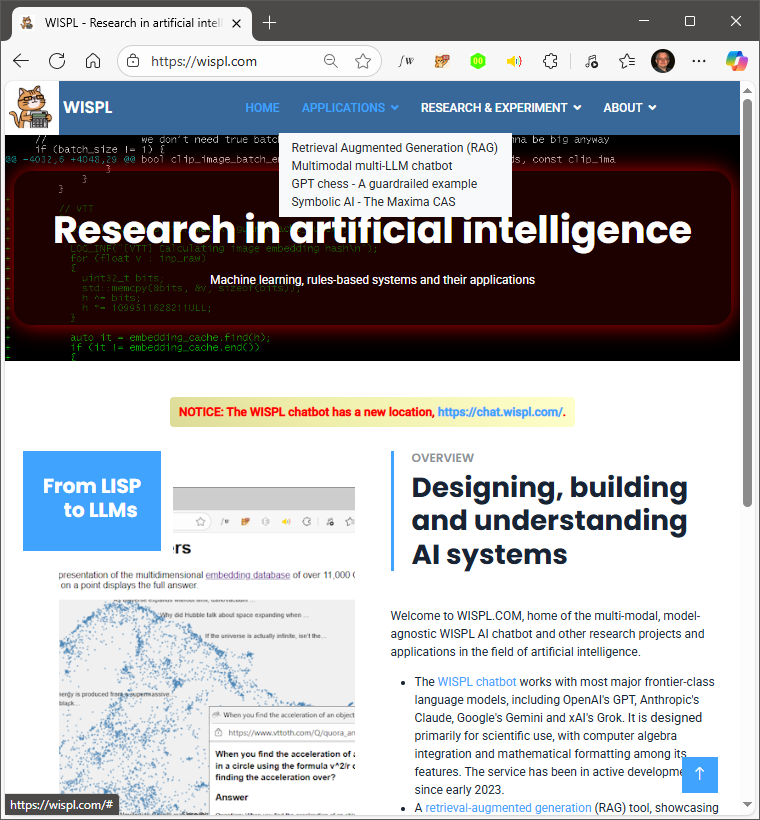

That settled it. For several months now, I’ve been exploring options. Which Linux? Go back to Slackware? A bit pedestrian but I am very fond of that distribution and it’s part muscle memory. Stay with RHEL/Oracle OS/Fedora? The server versions are a tad too conservative, and in any case, I don’t trust Red Hat anymore, not after what they’ve done to CentOS. Some of the CentOS successors? Again, not exactly for desktops. I also wanted a desktop running KDE, not Gnome, because I never really liked Gnome’s philosophy. Eventually, my searches and experiments allowed me to zero in on Debian: almost as old as Slackware, at least as respectable, and, well, a decent old school distro with a modern face.

I installed Debian 13 on my backup workstation four days ago. Earlier tonight, the big swap happened. With vacuum cleaner at hand (10-year old dust in places!) I swapped the backup and my primary workstation. So now I am sitting at my usual desk, typing on my worn keyboard, listening to Sirius XM on my computer… and apart from a few oddities, I no longer even notice that I am not on Windows.

Part of what made it possible of course is that today, my professional life is almost entirely operating system agnostic. I do very little development for Windows these days. It’s been months since I last fired up a version of Visual Studio. Mostly I target the Web, maybe writing back-end code in whichever language best suits the task, from Python to C++. Frankly, my biggest compatibility concern are my favorite games. But I’m sure I’ll find a way to run versions of Fallout, S.T.A.L.K.E.R., Metro, and a few more GOG games that I enjoyed playing from time to time.

Meanwhile, routine tasks work just fine, including my personal bookkeeping (using Microsoft Money 98 — yes, that ancient, since it contains my records going back almost 30 years.) I can also open just fine my Office files, including Visio diagrams, nontrivial Excel spreadsheets, and encrypted Word documents in LibreOffice. Besides, it’s not like my Windows 10 machine went anywhere. It’ll serve me as a backup box (workstation or server) likely for years to come. Until finally these old Xeon boxes either become truly obsolete or reach the end of their useful lives. But not because Microsoft forces me to ditch them.