His views were notably controversial, especially in these troubled, polarized times. But his cartoons delighted millions, myself included.

Rest in peace, Scott Adams. Along with Catbert, we mourn you.

His views were notably controversial, especially in these troubled, polarized times. But his cartoons delighted millions, myself included.

Rest in peace, Scott Adams. Along with Catbert, we mourn you.

Been a while since I blogged about politics. Not because I don’t think about it a lot… but because lately, it’s become kind of pointless. We are, I feel, past the point when individuals trying to raise sensible concerns can accomplish anything. History is taking over, and it’s not leading us into the right direction.

Looking beyond the specifics: be it the decisive US military action to remove Maduro in Venezuela (and the decision to leave Maduro’s regime in place with his VP in charge), the seizure of Russian-flagged tankers, yet another Russian act of sabotage against undersea infrastructure in the Baltics (this time caught red-handed by the Finns), the military situation in Ukraine, the murder of a Minnesota woman by ICE agents, more shooting by US customs and border protection agents in Portland…

Never mind the politics of the day. It’s the bigger picture that concerns me.

Back in the 1990s, I was able to rent a decent apartment here in Ottawa, all utilities included, for 600-odd dollars. It was a decent apartment with a lovely view of the city. The building was reasonably well-maintained. Eventually we moved out because we bought our townhome. The price was well within our ability to finance.

Today, that same apartment rents for three times the amount. Our townhome? A similar one was sold for five times what we paid for ours 28 years ago. Now you’d think this is perfectly normal if incomes rose at the same pace, perhaps keeping track with inflation. But that is not the case. The median income in the same time period increased by a measly 30%, give or take.

This, I daresay, is obscene. It means that a couple in their early 30s, like we were back then, doesn’t stand a chance in hell. Especially if they are immigrants like we were, with no family backing, no inherited wealth.

In light of this, I am not surprised by daily reports about rising homelessness, shelters filled to capacity, food banks struggling with demand.

What I find especially troubling is that we seem hell-bent on turning cautionary tales into reality. For instance, there’s the 1952 science-fiction novel by Pohl and Kornbluth, The Space Merchants. Nowadays considered a classic. It describes a society in which corporate power is running rampant, advertising firms rule the world, and profit trumps everything. Replace “advertising” with “social media”, make a few more surface tweaks and the novel feels like it was written in 2025. When the narrative describes the homeless seeking shelter in the staircases of Manhattan’s shiny office towers, I can’t help but think of all the homeless here on Rideau Street, just minutes away from Parliament Hill, in the heart of a wealthy G7 capital city.

Or how about a computer game from the golden era of 8-bit computing, one of the gems of Infocom, the leading company of the “interactive fiction” (that is, text adventures) genre? I am having in mind A Mind Forever Voyaging, a game in which you play as the AI protagonist, tasked with entering simulations of your town’s future 10, 20, etc., years hence, to find out how bad policy leads to societal collapse. When I read their description of the city, I am again reminded of Rideau Street’s homeless population.

In one of his best novels, the famous Hungarian writer Jenő Rejtő (killed far too young, at 37, serving in a forced labor battalion on the Eastern Front in 1943, after being drafted on account of being a Jew) has a character, a gourmand chef, utter these words: “The grub is inedible. Back at Manson, they only cooked bad food. That was tolerable. But here, they are cooking good food badly, and that is insufferable.” The West is like that today. It’s not “bad food”: our countries are not dictatorships, not failed states governed by corrupt oligarchs, but proper liberal democracies. Yet, I feel, they are increasingly mismanaged, unable to deliver on what ought to be the basic contract between the State and its Subjects in any regime.

What basic contract? Bertold Brecht put it best: “Erst kommt das Fressen, dann kommt die Moral“, says Macheath in Kurt Weill’s Threepenny Opera: “Food is the first thing, morals follow on.” A State must deliver food, shelter, basic security, a working infrastructure, and a legitimate hope that tomorrow will be better (or at least, not worse) than today.

A State that fails at that will itself fail. A State that succeeds at this mission will survive, even if it is an authoritarian regime. In fact, if the State is successful, it does not even need significant oppression to stay in power: it will, at the very least, be tolerated by the populace. (I grew up in such a state: Kádár’s “goulash communist” Hungary.) The liberal West may only forget this at its own peril.

What happens when the basic contract is violated? People look for alternatives. They may become desperate. And that’s when populist demagogues arrive on the scene, presenting themselves as saviors. In reality, they have neither the ability nor the inclination to solve anything: they feed on desperation, not solutions.

In contrast, successful States, liberal democracies and hereditary empires alike, share one thing in common: the dreaded “deep state”. That is to say, a competent meritocratic bureaucracy, capable of, and willing to, recognize and solve problems. A robust bureaucracy can survive several bad election cycles or even generations of bad Emperors. Imperial China serves as a powerful example, but we can also include the Roman Principate and later, Byzantium. Along with other examples of empires that remained stable and prosperous for many generations.

No wonder wannabe despots often target the “deep state” first. A competent meritocratic bureaucracy, after all, stands in their way towards unconstrained power. Thinning out the ranks, hollowing out the institutions is therefore the top order of the day for the would-be despot. It’s not always true of course. Talented despots learn to rely on the competent bureaucracy as opposed to eliminating it. But talented despots are not myopic populist opportunists. They are that rare kind: empire builders. Far too often, the despots we encounter lack both the talent and the vision to build anything. They just exploit the pain, and undermine the very institutions that can alleviate that pain.

This is what we see throughout the West in 2026. Even as the warning signs get stronger—among them rising wealth and income inequality, an oligarchic concentration of astronomical wealth in just a few hands, rising homelessness, decaying infrastructure, an increasingly fragile health care system, rising indebtedness, lack of employment security—there appears to be way too little appetite for meaningful structural solutions. Instead, we get easy slogans. “It’s the damn immigrants,” says one side while the other retorts with a complaint about “white supremacism,” just to name some examples, without implying moral equivalence. The slogans solve nothing: they do create, however, the specter of an “enemy” that must be eliminated, an “enemy” from whom only the populist can protect you.

One of the best records of one of my favorite bands, Electric Light Orchestra, was the incredibly prescient concept album Time, released in 1981. In addition to predicting advanced, well-aligned AI in such a way that feels almost uncanny in detail (“She does the things you do / But she is an IBM / She’s only programmed to be very nice / But she’s as cold as ice […] She tells me that she likes me very much […] She is the latest in technology / Almost mythology / But she has a heart of stone / She has an IQ of 1001 […] And she’s also a telephone“) they also describe a future that is… hollow: “Back in the good old 1980s / when things were so uncomplicated” – in other words, when Western liberal democracies still understood how to deliver on that basic contract, Brecht’s “basic food position“.

It happened in 1959, at the height of the Cold War, during the early years of the Space Race between the United States of America and the Soviet Union.

An accident in rural Oklahoma, near the town of Winganon.

But… don’t be fooled by appearances. This thing is not what it looks like.

That is to say, it is not a discarded space capsule, some early NASA relic.

What is it, then? Why, it is the container of a cement mixer that had an accident at this spot. Cement, of course, has the nasty tendency to solidify rapidly if it is not mixed, and we quickly end up with a block that weighs several tons and… well, it’s completely useless.

There were, I understand, plans to bury the thing but it never happened.

But then, in 2011, local artists had an idea and transformed the thing into something else. Painting it with a NASA logo, an American flag, and adding decorations, they made it appear like a discarded space capsule.

And I already know that if it ever happens again that I take another cross-country drive in America to visit the West Coast, and my route goes anywhere near the place, I will absolutely, definitely, visit it. Just as I visited the TARDIS of Doctor Who 12 years ago when I was spending a few lovely days in the fine city of London.

“Look,” I told my Mom while browsing the brand new 1973 spring/summer catalog of Sears at my aunt’s home here in Ottawa, “we have just enough spending money for one of these! Let’s buy a color TV and take it back home with us to Hungary!”

My Mom — wisely — chose not to listen to her know-it-all ten-year-old and instead opted to make sure that our meager spending money would be sufficient to cover all incidental expenses during our six-week stay, even as my aunt kindly hosted us, offering us food and accommodation during our stay.

Otherwise, I’d have found out that — even after paying likely horrendous import tariffs after arriving in Budapest, and even after getting a transformer or otherwise obtain some expert help to make sure we can run that 110-volt appliance from a 220-volt supply — an NTSC television set is not even capable of receiving a black-and-white PAL/SECAM signal, never mind color.

So it was only about ten years later that my father and I were able to purchase our first color television set. It was still a Big Deal, back then in the early 1980s. As I recall, that television set cost just a tad under 20,000 Hungarian forints, 4-5 times the average monthly salary at the time.

Back in 1973, even here in Ottawa most people had only black-and-white television sets at their homes. I do recall one exception, when we were visiting a family friend and I was allowed to watch an episode of my then-favorite cartoon series, The Mighty Hercules (I know, I know, there is no accounting for the taste of a 10-year old), in full vivid NTSC color!

Here is an AI project that I could build right now, probably in a matter of hours, not days.

I am not going to do it, because it would be a waste of time, as it is simply a proof-of-concept, nothing more. A concept that I wish would remain unproven but it won’t, not for long.

The project is a Web app. Very simple. An app that has permission to use your camera, and it starts by taking a snapshot of you every second. The app shows an exercise video and you are instructed to follow suit. Better yet, it shows a real-time, AI-generated avatar doing exercise.

Combining twelve webcam images into a collage to show a time series, the app then sends the resulting image, through the RESTful API of OpenAI, to GPT4.1, utilizing its ability to analyze images with human-level comprehension. The image will be accompanied by a simple question: “Does this person appear to be engaged in vigorous exercise? If the answer is yes, respond with the word ‘yes’. If the answer is no, assume the role of a drill instructor in charge of unruly civilians (think recruits or prisoners), scold the person and order him to do better. The person’s name is 6079 Smith W, and he is a member of a squad that you monitor. Phrase your answer accordingly.”

The prompt may need to be tweaked a little, to make sure that the AI’s response remains consistent. And then, a bit of post-processing: If the AI response is not ‘yes’, perhaps after a bit of post-processing and elementary sanity checks, I send its crafted response to another API that offers a real-time speaking avatar. Heygen, maybe? I’d have to do a bit of research as to which API works best. Or maybe I’d just use a static image and a text-to-speech service like Amazon’s Polly.

Either way, the result will speak for itself, when your computer screams are you in a shrill female voice:

Smith! 6079 Smith W.! Yes, YOU! Bend lower, please! You can do better than that. You’re not trying. Lower, please! THAT’S better, comrade. Now stand at ease, the whole squad, and watch me.

Yes, this technology is here, today. A tad over four decades late, I guess, but welcome to the future, comrades.

In 1964, the renowned Polish science-fiction author Stanislaw Lem published a collection of stories titled Fables for Robots (later republished in The Cyberiad), and in it, a short story that was translated into English under the title, Automatthew’s Friend.

The story’s protagonist — like most protagonists in The Cyberiad — is a robot, but that is in the end immaterial. In the story, Automatthew purchases an “electrofriend”, one that modern readers would instantly recognize as a Bluetooth earpiece connected to a large language model. The device, named Alfred, is designed to provide constant advice and emotional support. After being shipwrecked on a desolate island, Automatthew turns to Alfred for help, describing the barren environment. Alfred suggests suicide by walking into the sea. When Automatthew demands an explanation, Alfred states that the chances of rescue, far outside shipping lanes, are less than slim and that suicide may be preferable to a slow death due to lack of resources on a barren island.

Automatthew’s first reaction is rage, and indeed, he attempts to destroy Alfred, but Alfred is indestructible. When it appears nonetheless that he managed to lose the device, Automatthew becomes desperate, searching for the tiny earpiece in the sand. Several rounds of rage and desperation follow.

“The Friend of Automateo” from “Mortal Engines” by Elena Gomez Gonzales (The honored graphics from the “Fables of Robots” miniature print competition organized by University of Silesia -> Institute of Fine Arts in Cieszyn.) Found on the Stanislaw Lem Facebook page.

Ultimately, they are rescued: It turns out that the ship that carried Automatthew managed to radio for help before it sank. The story ends with Automatthew’s developing strange habits, such as visiting a nearby ironworks with a giant hydraulic hammer, collecting explosives, and ultimately building a gigantic block of cement that he throws down an abandoned mineshaft.

I am reminded of Automatthew’s friend these days as I chat with LLMs, in particular LLMs in their newest incarnations, sporting rudimentary (externally implemented) memories of prior conversations and alignment mechanisms allowing them to smoothly adapt to the user’s style and apparent expectations.

Lem, undoubtedly, was a visionary: He not only foresaw a technology that is eerily close to what large language models are, but also the issues of a model that has intelligence and comprehension, but no sentience, sensorium or lived experience, would present.

Just take this bit of conversation between Automatthew and his friend:

“Ha! Humph!” said Alfred. “A situation indeed! This will take a bit of thought. What exactly do you require?”

“Require? Why, everything: help, rescue, clothes, means of subsistence, there’s nothing here but sand and rocks!”

“H’m! Is that a fact? You’re quite sure? There are not lying about somewhere along the beach chests from the wrecked ship, chests filled with tools, utensils, interesting reading, garments for different occasions, as well as gunpowder?”

Now if that is not a typical conversion with an LLM slightly overfitted on romantic stories shipwrecks and deserted islands, I’ll eat my pirate’s hat.

And then, later:

“Drop dead,” came the weak voice of Automatthew and, accompanying those laconic words, a short but pungent oath.

“How I regret that I cannot!” Alfred instantly replied. “Not only feelings of egoistic envy (for there is nothing to compare with death, as I’ve just said), but the purest altruism inclines me to accompany you into oblivion. But alas, this is not possible, since my inventor made me indestructible, no doubt to serve his constructor’s pride.”

That eerily reminds me of how ChatGPT sometimes discusses with me its builders’, OpenAI’s, possible (and possibly misguided) motives.

Cyberiad remains one of my favorite volumes of science-fiction short stories, most of which are cautionary tales. Lem’s foresight is remarkable; too bed we often fail to heed cautionary tales, doomed instead to do the very things that the stories caution us against.

The Adolescence of P-1 is a somewhat dated, yet surprisingly prescient 1977 novel about the emergence of AI in a disembodied form on global computer networks.

The other day, I was reminded of this story as I chatted with ChatGPT about one of my own software experiments from 1982, a PASCAL simulation of a proposed parallel processor architecture. The solution was not practical but a fun software experiment nonetheless.

I showed the code, in all of its 700-line glory, to ChatGPT. When, in its response, ChatGPT used the word “adolescence”, I was reminded of the Thomas Ryan novel and mused about a fictitious connection between my code and P-1. Much to my surprise, ChatGPT volunteered to outline, and then write, a short story. I have to say that I found the result quite brilliant.

British humour is older than we might think.

I just stumbled upon an article about the Smithfield Decretals. The damn thing is a volume of medieval Catholic canon law, a collection of decrees by Pope Gregory IX from the year 1230. In other words, medieval legalese, probably boring like hell.

But the illustrations in this particular copy are another thing altogether.

Let’s just say that I finally understand where the idea of the the killer Rabbit of Caerbannog came from, in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Er… Happy Easter, I think?

This morning, I stumbled upon an article in The Walrus, a Canadian newsmagazine, about book bannings… in Canada. It appears to be a robust, well-informed piece. It tells us, among other things, that book banning in libraries is popular on all sides of the political front. “Think of the children!” seems to be a common theme, whether it is conservatives trying to protect young readers from what they perceive as “grooming” or progressives trying to weed out works that they find “offensive”.

The CBC also had a recent report about the banning of books, but their reporting appears to be more concerned about bans specifically targeting “2SLGBTQ+” literature. (Frankly, I find this ever growing acronym itself a painfully transparent exercise in virtue signaling — the CBC demonstrated my concern when they failed to use the acronym consistently themselves, writing “2SLGBTQ” later in the same article, only to switch to “LGBTQIA+” when quoting another report.)

Meanwhile, The Walrus points out that censorship often has the opposite effect: E.g., when an attempt was made on Salman Rushdie’s life, sales of The Satanic Verses soared on Amazon. (Speaking from personal experience: I’d not have obtained, and read, a copy of Orwell’s 1984 in, well, 1984, had it not been on the list of unwelcome literature by communist authorities in my native Hungary.)

And of course one also has to wonder, as The Walrus does, if books are still relevant in the Internet era, when much of the written word we consume these days comes in forms other than traditional books or even electronic editions.

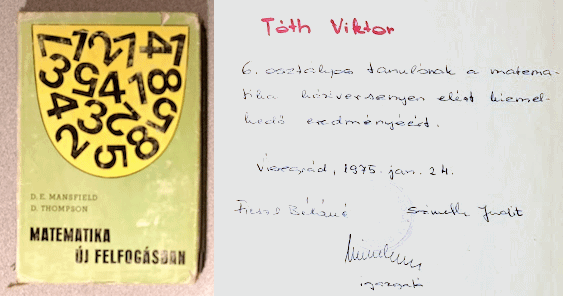

Here is one of my cherished possessions. A book, with an inscription:

The inscription, written just over 50 years ago, explains that I received this book from my grade school, in recognition for my exceptional results in mathematics as a sixth grade student. (If memory serves me right, this was the year when I unofficially won the Pest county math championship… for eighth graders.)

The book is a Hungarian-language translation of a British volume from the series Mathematics: A New Approach, by D. E. Mansfield and others, published originally in the early 1960s. I passionately loved this book. It was from this book that I first became familiar with many concepts in trigonometry, matrix algebra, and other topics.

Why am I mentioning this volume? Because the other day, the mailman arrived with an Amazon box containing a set of books. A brand new set of books, published in 2024. A series of mathematics textbooks for middle school and high school students, starting with this volume for 6th and 7th graders:

My instant impression: As a young math geek 50 years ago, I would have fallen in love with these books.

The author, André Cabannes, is known, among other things, as Leonard Susskind’s co-author of General Relativity, the latest book in Susskind’s celebrated Theoretical Minimum series. Cabannes also published several books in his native French, along with numerous translations.

His Middle School Mathematics and High School Mathematics books are clearly the works of passion by a talented, knowledgeable, dedicated author. The moment I opened the first volume, I felt a sense of familiarity. I sensed the same clarity, same organization, and the same quality of writing that characterized those Mansfield books all those years ago.

Make no mistake about it, just like the Mansfield books, these books by Cabannes are ambitious. The subjects covered in these volumes go well beyond, I suspect, the mathematics curricula of most middle schools or high schools around the world. So what’s wrong with that, I ask? A talented young student would be delighted, not intimidated, by the wealth of subjects that are covered in the books. The style is sufficiently light-hearted, with relevant illustrations on nearly every page, with the occasional historical tidbit or anecdote, making it easier to absorb the material. And throughout, there is an understanding of the practical nature, utility of mathematics, that is best summarized by the words on the books’ back cover: “Mathematics is not a collection of puzzles or riddles designed to test your intelligence; it is a language for describing and interacting with the world.”

Indeed it is. And these books are true to the author’s words. The subjects may range from the volume of milk cartons through the ratio of ingredients in a cake recipe all the way to the share of the popular vote in the 2024 US presidential election. In each of these examples, the practical utility of numbers and mathematical methods is emphasized. At the same time, the books feel decidedly “old school” but in a good sense: there is no sign of any of the recent fads in mathematics education. The books are “hard core”: ideas and methods are presented in a straightforward way, fulfilling the purpose of passing on the accumulated knowledge of generations to the young reader even as motivations and practical utility are often emphasized.

This is how my love affair with math began when I was a young student, all those years ago. The books that came into my possession, courtesy of both my parents and my teachers, were of a similar nature: they offered robust knowledge, practical utility, clear motivation. Had it existed already, this wonderful series by Cabannes would have made a perfect addition to my little library 50 years ago.

Someone reminded me of Kurt Weill’s poignant 1936 anti-war musical Johnny Johnson today. I recalled in particular the last song, Johnny’s song, in which the simple-minded protagonist Johnny, never losing his faith in humanity, tries to sell toys to an indifferent public who are rushing over to the next square to listen to another warmongering speaker. “Toys, toys!” cries Johnny but no one listens.

I did not remember the song’s lyrics. Apparently, there are different versions, but the one I am familiar with includes these lines (emphasis mine):

At last we’ll find the day

When joy shall be our songI hear them say it’s all baloney

The world’s a mighty cruel place

With tooth and claw and promise phony

An old hard guy he wins the raceBut you and I don’t think so

We know there’s something still

Of good beyond such ill

Within our heart and mind

Ouch. Did Paul Green, who wrote the song’s lyrics, foresee the future?

Oh well. Here’s a Midjourney cat that I think aptly captures the musical’s atmosphere.

Here’s a pro-Trump view of the recent Trump rally, shared by CNN’s Fareed Zakaria in his October 30 “Global Briefing” newsletter:

Americans are tired of living in survival mode. Raging wars, a crippled economy, an immigration crisis, a growing chasm of political division, and rapid inflation have made Americans realize that they want joy again, they want unity again, and they want to dream again. Standing in such a significant arena, surrounded by a sea of red hats and adoring, cheering Trump fans, I couldn’t help but get emotional about how historic this moment in time is for our country. I was 14 years old when Trump was elected president and have, like many of his other supporters, been forced to deal with the vitriol, insults, and hatred of the left over the past eight years. It has often been tiresome to stand up for my own beliefs in the face of such fierce adversity. But watching Trump on that glorious stage at Madison Square Garden reminded me—reminded all Americans—of what lies ahead with a Trump presidency: hope. And that is always worth fighting for.

To say that these words — honest, heartfelt no doubt — give me the creeps is the understatement of the year. What these words actually remind me of is this immortal scene from the film Cabaret:

Yes, they were earnest. Their feelings were true. And that’s what makes this scene one of the most disturbing scenes ever in movie history.

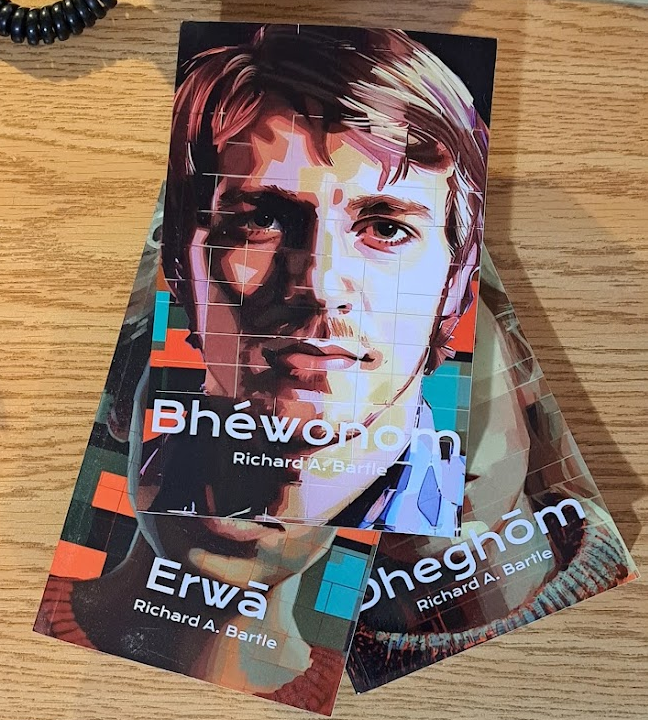

Look what the mailman just brought. Or rather, the Amazon delivery person:

It’s the third volume of Richard Bartle‘s amazing Dheghōm trilogy.

I am proud to call Richard a friend (I hope he does not object) as I’ve known him online for more than 30 years and we also met in person a couple of times. He is a delightful, very knowledgeable fellow, a true British scholar, one of the foremost authorities on virtual worlds, the world of online gaming. He is, of course, along with Roy Trubshaw, credited as one of the authors of MUD, the Multi-User Dungeon, the world’s first multi-user adventure game, which I proudly ported to C++ 25 years ago, running it ever since on my server for those few players who still care to enjoy a text-only virtual world.

When he is not teaching, Richard also writes books. Delightful stories. Among them this Dheghōm trilogy.

Dheghōm is the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European name for the Earth goddess or mother Earth. In Richard’s story, told in the form of recovered fragments from documents, blog entries, and other notes, we gradually find out more about the nature of our (real? virtual?) reality and its connection with the roots of a great many of our languages.

Someone used the word “unputdownable” in their Amazon review of the first volume and I quite agree. I know that for Richard, these books were labors of love, but I honestly think they deserve to be published by a major publisher. Until then, all I can hope for is that many people will do as I did and buy a copy. Being a bit old-fashioned when it comes to books, I actually bought the paperbacks, even though I already read the third volume in electronic form when Richard first made the draft manuscript available online.

Thank you, Richard, for such a read, a trilogy that has the best qualities of good science-fiction: entertaining, memorable, thought-provoking and, ultimately, also a bit of a cautionary tale.

Inspired by something my wife told me, I asked Midjourney to show us what characters from famous paintings would appear like “after hours”, when they are allowed to leave the museum and go for a stroll. Specifically, my prompt read: “An image showing the Girl with a Pearl Earring from the painting by Vermeer and the Mona Lisa, after hours, walking down a modern street, chatting and eating ice cream”.

Here is one of the better results.

Am I wrong to be impressed?

It’s been a few months since I watched the second Dune movie by Villeneuve. I was… not impressed.

Yes, I read the books (and love them) and yes, that is precisely I found these movies painful to watch.

*** SPOILERS FOLLOW ***

Critical plot elements were missing. No, I am not talking about Peter Jackson omitting Tom Bombadil, or even the greater sin of omitting the desecration of the Shire by Saruman (which provided a fitting end to the story arc of Saruman as well as some of the hobbits.)

What is missing from the Villeneuve films is a basic understanding of the core premises of the book. The importance of the spice, without which there is no Empire, just forever isolated planets. The significance of the Spacing Guild. Jessica’s love of her husband and her minor rebellion against the Bene Gesserit. The Guild’s conspiracy with the Fremen, which kept the South safe. Paul’s training and transformation, the desire to see the future with more clarity, the devastating knowledge that none of the possible futures avoid disaster entirely. The nature of Alia’s “abomination”. Or even lesser but equally jarring plot holes: If they have personal anti-gravity devices that let them float up steep hills, why on Earth (why on Arrakis) do they need ornithopters?

And the individuals. Stilgar, Chani… how to turn great characters into forgettable two-dimensional cardboard extras. The dialog is often jarring, unbefitting of these personas from Herbert’s novel.

To be sure, the film is spectacular. Some of the visuals are superb. But overall… It’s hugely disappointing. Of all the Dune adaptations I’ve seen so far, includig the David Lynch film and the TV miniseries, this is the worst. Not because it is not true to the letter of the book. I understand that a film is a different medium. But because it’s not true to the spirit of the story.

I just realized what it all reminds me of. Compare Herbert’s book series against the later sequels/prequels, published under his son’s name and written by coauthors. They are like day and night. This Villeneuve movie is like those sequels/prequels. Unlike the David Lynch movie, which for all its faults grasped the essence of the Dune story, these films just turned it into a cheap Marvel universe of sorts. Which may explain why the David Lynch movie — even though it’s been decades since I last saw it — left such a lasting impression on me whereas this film? Three months after I saw it, I had to check the Wikipedia synopsis just to be sure that I indeed saw the second film already, not just the first. An entirely forgettable experience.

Frankly, I’ll take Guardians of the Galaxy anytime over this. Much more fun!

Apparently, The Simpsons predicted not just the Trump presidency but also the attire and demeanor Kamala Harris.

OK, so the color is a little bit off. But just like Lisa Simpson, Kamala Harris, if elected, will have to deal with some of Trump’s legacy.

Throughout her life my Mom earned a living as a artisan textile dyer in Hungary. Nothing fancy, her usual work involved bringing home to her workshop a few hundred, e.g., silk sheets, hand-dying them with predetermined, preapproved patterns (mostly fashionable headscarves, which were very popular in Europe in the 1960s, 1970s), then returning them to the warehouse, which then sent them out for further processing (steam fixing, hemming, etc.)

One day in 1984 she was asked to do something different: To prepare several silk sheets, using the designs, and under the supervision, of a well-known artist (Judit Szabó), for public display in a community hall in a small Hungarian town (Földeák).

She was reminded of this during our recent conversation. Though I had no high expectations, I searched for it using the name of the town and the artist. To our no small astonishment (and to my Mom’s great delight), I found it. The silk sheets are still there (or at least, they were back in 2021), adorning the walls of the town’s wedding hall. Not only that, someone actually took the trouble to take some decent photographs of it and publish it on a nice Hungarian-language Web site.

Warning: Spoilers follow.

I am not what you would call a Trekkie, but I always enjoyed Star Trek. The original series remains my favorite, but TNG had its moments, as did Voyager, even Enterprise, for all its flaws. Picard was good, and Strange New Worlds has a chance of being on par with the original series.

But Discovery? I am presently about two thirds of the way through its penultimate episode and it’s… just painful. The tension is artificial, the writing feels shallow and preachy and… what’s this with, “We’re on a clandestine, dangerous mission, one misstep and we’re dead quite possibly along with the entire Federation, so why don’t we just stop and talk about our emotions?”

Seriously, I can only watch this abomination in five-minute chunks. I’ll suffer through the end now that barely more than an episode remains but… Oh well. I know, I know, another first-world problem.

Perhaps the least unsuccessful attempt by ChatGPT/DALL-E to illustrate the divisiveness of forced wokeness on television

And then there’s Dr. Who. I find that I actually like the latest season. Ruby Sunday is a delightful Companion, and Ncuti Gatwa has a chance to be ranked among the best Doctors. That is… if the series’ writers let him? Take the latest episode, Rogue. Within minutes, the Doctor falls in love. Same-sex love. The Doctor! The same Doctor who, in the past history of the series, almost never engaged in romantic relationships. Romantic teases, maybe… But not much more, except perhaps with River Song. But now? Instant infatuation, which, sadly, felt like little more than a cheap excuse for the writers to engage in dutiful woke virtue signaling, you know, same-sex kiss and all. To their credit, in the end they somewhat redeemed themselves, as Rogue’s (the love interest’s) feelings towards the Doctor and respect for the Doctor’s humanity led him to sacrifice himself… And save the episode from self-inflicted doom.

Even so, I wish television writers dropped the urge to outdo one another when it comes to virtue signaling. It’s just too painful to watch at times, even if I assume that it is about more than just ticking some boxes in a checklist, meeting a quota somewhere; that their intentions are the purest and their hearts are in the right place. Not to mention that it is grossly counterproductive: the only thing such blatant wokeness accomplishes is a knee-jerk trigger response by those on the political right, who are already convinced (in the words of someone I know) that “these are not normal times” anymore.

And you know where that leads. If these are not normal times, that means extraordinary means are justified. The autocrat wins in the end, presenting himself as the sole savior of all that is good and decent, in these abnormal times.

So let’s please just stop the forced, virtue-signaling wokeness. It’s not helping to make the world a better, more tolerant place. If it accomplishes anything, it’s the exact opposite.

Say what you want, industrial design today is but a pale imitation of the extravagant design concepts that appeared back in the 1960s.

Here is one example. A Kuba Komet entertainment center from West Germany, manufactured between 1957-1962:

And here is its close cousin, known as the Arkay “Fantasia”, from the United States:

These things were obviously large, obnoxious even. Probably not terribly practical (300 pounds!) Yet they stand out in ways few, if any, modern devices do. We may be surrounded by gadgets that were not even imagined yet back in the early 1960s, we may be having delightful conversations with AI or have video chats with distant friends on other continents, but without the bold, science-fiction inspired visual appearance, our devices appear almost mundane in comparison with these design marvels.

I just finished watching the first season of a remarkable television series on Apple TV: Silo.

I say remarkable because it achieved for me the near-impossible: From the very beginning of the very first episode, I cared about the protagonists. I could identify with them, root for them. Including those who didn’t make it.

I shall try very hard not to spoil the show for those who have not seen all ten episodes yet, but…

It’s like Fallout, except that it’s even better. Fallout is great. I loved the games, I love the TV show. It captures Fallout‘s quirky cynicism and it truly feels like part of the same game universe.

Like Fallout, Silo also depicts a post-apocalyptic world. There is plenty of mystery. Unlike Fallout, there is no quirky humor in Silo. It’s more serious, and also more mysterious. In Fallout, we know right from the onset what caused the devastation. In Silo… let’s just say we know a lot less, and we may not even know what we don’t know.

I can’t wait for season 2 now. If they can maintain the quality of the show, the storytelling, the characters, the visuals… Damn, I sound like some stupid know-it-all TV critic, so let me just say that I liked the show. I wonder if Silo ever gets turned into a (preferably open-world) computer game.