A few days ago, I was in for a shock. Something I held as absolutely true, something that seemed self-evident in general relativity turned out to be blatantly wrong.

We learn early on that there is no dipole gravitational radiation, because there is no such thing as intrinsic gravitational dipole moment. Gravitational radiation is therefore heavily suppressed, as the lowest mode is quadrupole radiation.

Therefore, I concluded smartly, an axisymmetric system cannot possibly produce gravitational radiation as it does not have a quadrupole mass moment. Logical, right? Makes perfect sense.

Wrong.

What is true is that an axisymmetric system that is stationary – e.g., a rigid, axisymmetric rotating object with an axis of rotation that corresponds to its symmetry axis – will not radiate.

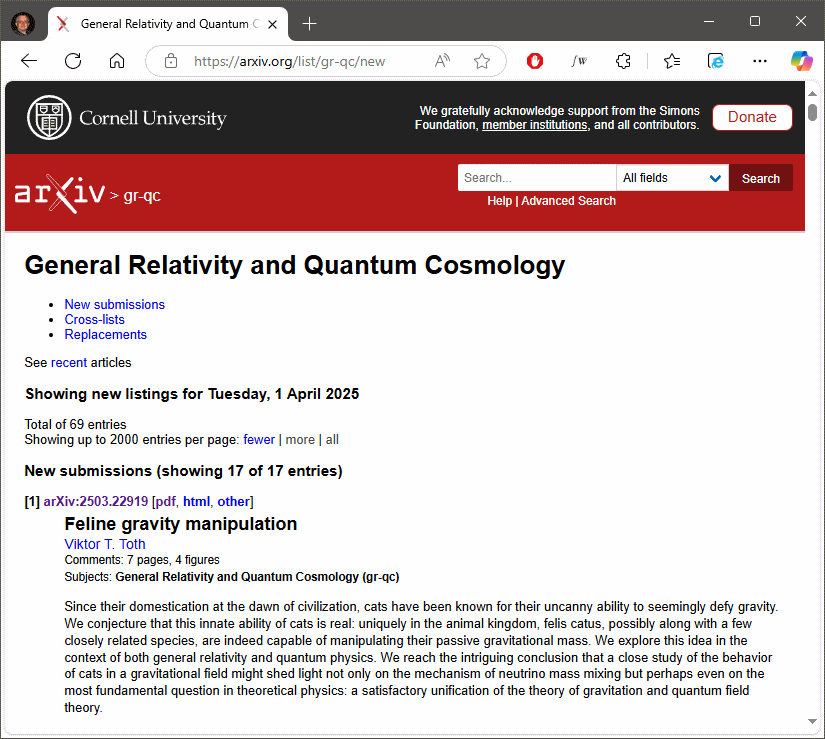

But two masses in a head-on collision? They sure do. There is even literature on this subject, some really interesting papers going back more than half a century. That’s because there is more to gravity than just the distribution of masses: there’s also momentum. And therefore, the gravitational field will have a time-varying quadrupole component even as the quadrupole mass moment remains zero.

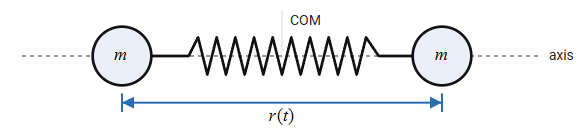

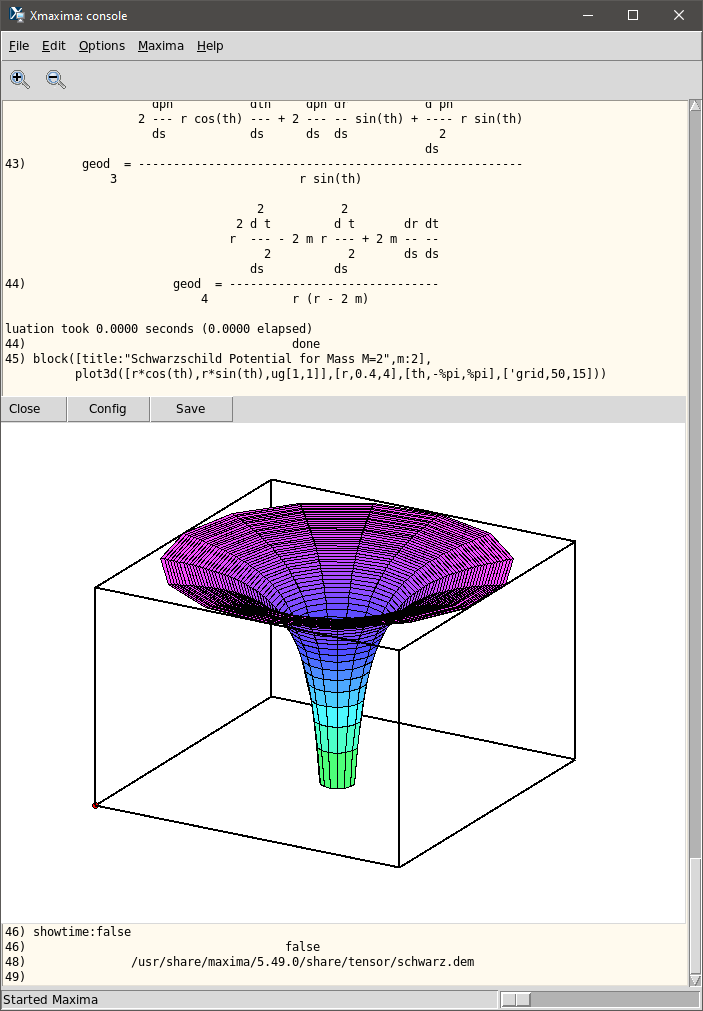

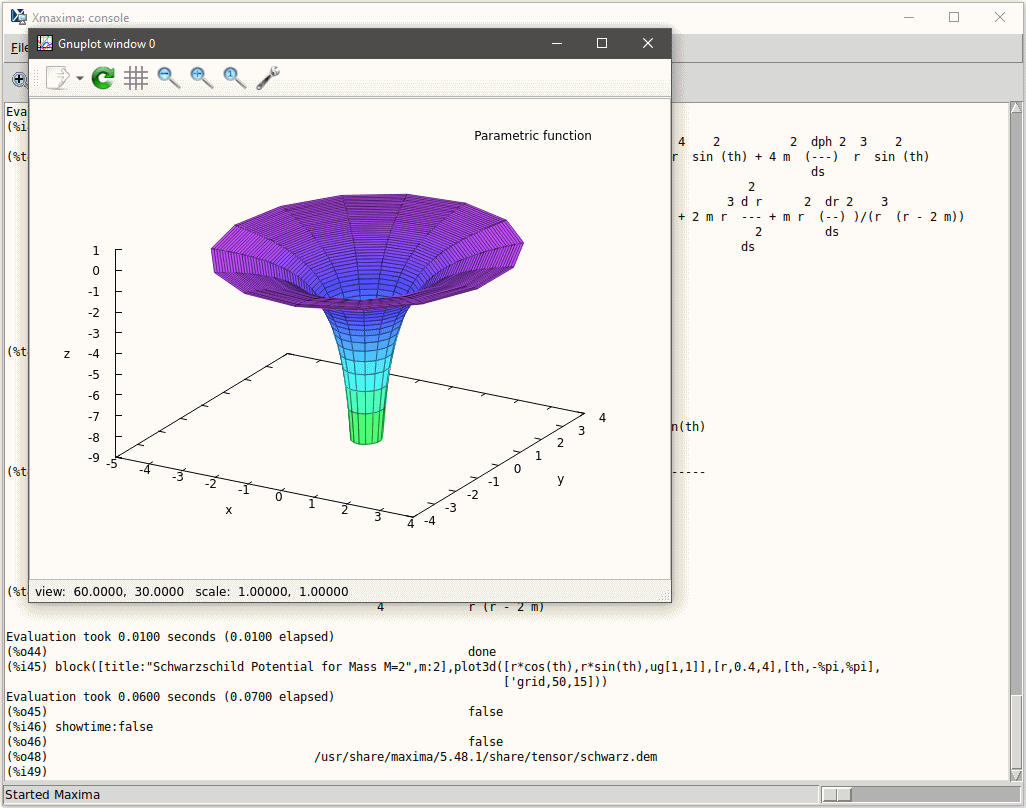

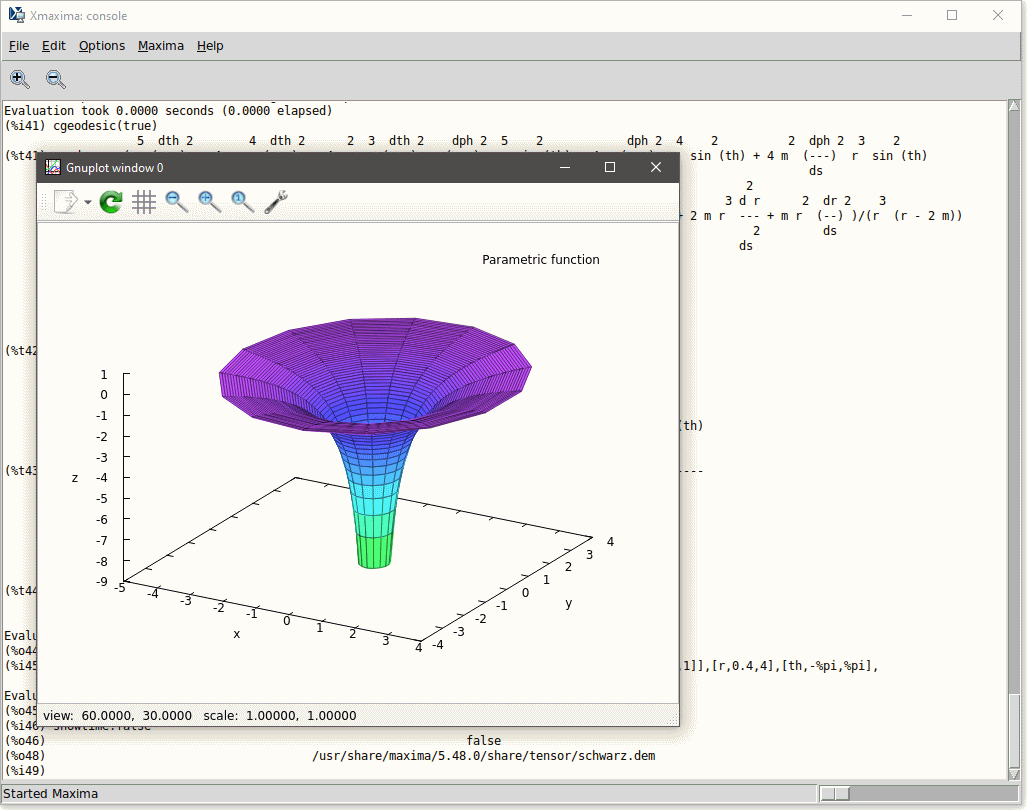

So I took it upon myself to calculate a simple, pedagogical case: two masses on a spring, bouncing back-and-forth without rotation. A neat, clean, nonrelativistic case, which can be worked out in an analytic approximation, without alluding to exotics like event horizons, without resorting to opaque numerical relativity calculations.

Yes, this system will produce gravitational radiation. Not a lot, mind you, but it will.

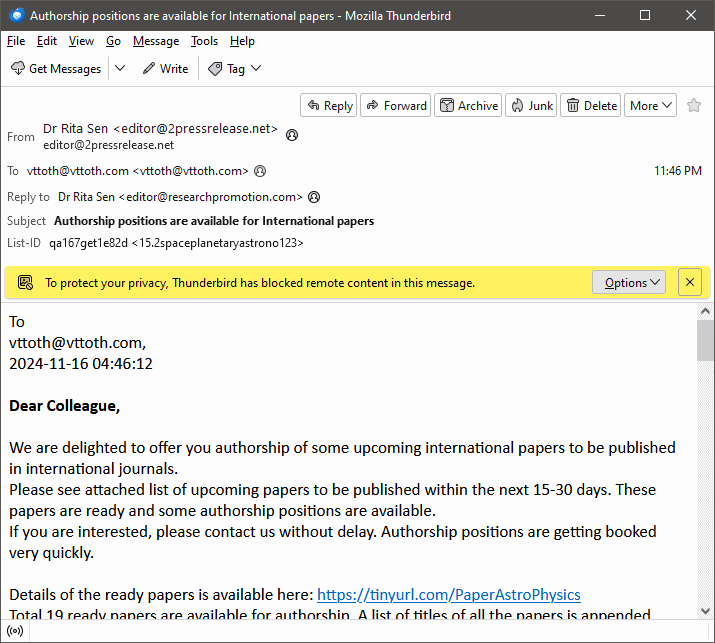

Once I understood this, I had another concern however. Over the years, surely I must have written answers on Quora promoting my flawed understanding? Yikes! How do I find those answers?

Oh wait. Not too long ago, I built a RAG: a retrieval augmented generation AI demo, which shows semantic (cosine similarity) searches using the totality of my over 11,000 Quora answers up to mid-2025 as its corpus. That means that I can interrogate my RAG solution and that would help me find Quora answers that no keyword search could possibly uncover. So I did just that, asked my RAG a question about axisymmetry and gravitational radiation, and presto: the RAG found several answers of mine, three of which were wrong, one dead wrong.

These are now corrected on Quora. And this exercise demonstrated how RAG works in an unexpected way. Note that the RAG answer is itself wrong, in part because it is faithfully based on my own incorrect Quora answers. Garbage in, garbage out. In this case, though, it meant that the same cosine similarity search zeroed in on my most relevant wrong answers. In an almost picture-perfect demonstration of the utility of a RAG-based solution, it saved me what would likely have amounted to hours of fruitless searching for past Quora answers of mine.