Recently, it felt at times almost like a fad: Questioning the legacy of past celebrities, removing statues, renaming institutions.

Often, it seemed like these denounced heroes of the past are held to an impossible standard: Not living up to the changing values of the present.

I questioned the motivation: Was it true concern that we worship the wrong heroes, or just a cheap attempt at “virtue signaling”? I questioned the outcome: Exactly how does renaming a high school or removing a statue from a public park help an Indigenous community get safe drinking water, better jobs, better health care?

But more importantly, I questioned the wisdom of judging the past by the standards of the present. Standards that evolve and (thankfully!) improve, but which, for that very reason, would have been impossible for our past heroes to live up to, as those standards did not yet exist.

Faced with the discovery of the unmarked graves of many hundreds of Canadian children that is reopening the wounds of the despicable residential school system, I was wondering the same thing. Were these schools really the manifestations of evil? Or were they perhaps no different from other residential schools for the poor, for the children of immigrants, for other disadvantaged members of a society that, let’s face it, was quite bigoted by present-day standards?

But now I have my answer. What took place in those schools a century ago was not normal, not acceptable. It was criminal, even by the standards of early-1900s Canada. It’s just that nobody cared.

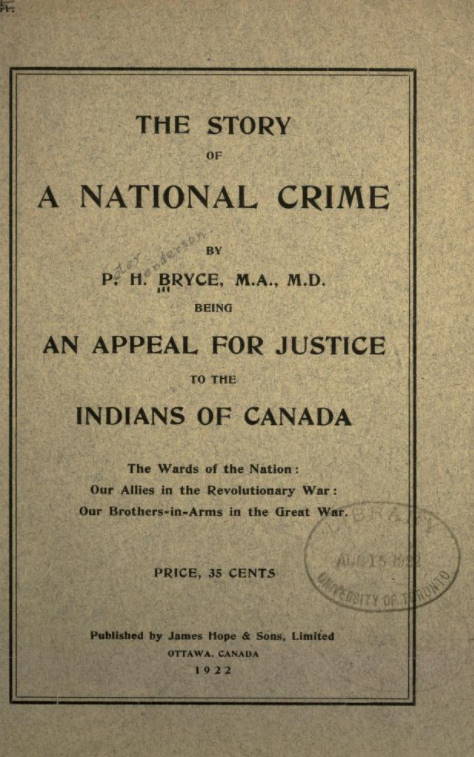

How do I know? From the accounts of someone who was in a unique position to critique the system: Peter Henderson Bryce, who at one point served as Canada’s Chief Medical Officer at the Department of Immigration.

For many years, Bryce studied the health of Canada’s Indigenous population, specifically the conditions at the residential schools. He was appalled by what he saw as an underfunded system of unsanitary, crowded facilities with shockingly high mortality rates. His report was suppressed and he was instead eventually pushed out of the Civil Service. Refusing to be silenced, he published his report himself.

The title says it all:

A National Crime

So there we have it. We are not misapplying our much improved, enlightened standards of 2021 to judge people and institutions that existed a century ago. What they did back then, how they treated the Indigenous population of Canada was A National Crime even by the standards of a contemporary member of the establishment, a dedicated civil servant who was already a teenager when the Dominion of Canada was established in 1867.

Dr. Peter Bryce, M. D., who passed away in 1932 at the age of 78, is buried not far from our home, right here in Ottawa, in the famed Beechwood Cemetery.