I again played a little with my code that implements a functional user interface to play chess with language models.

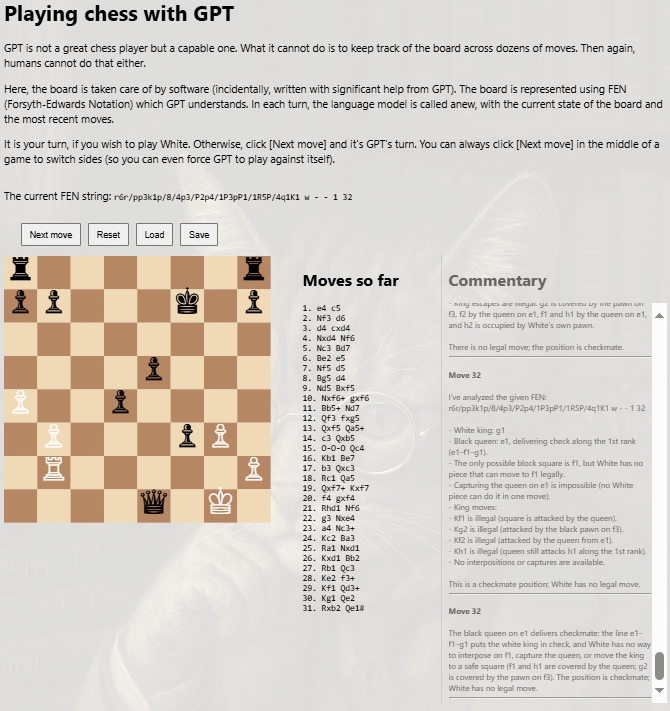

This time around, I tried to play chess with GPT-5. The model played reasonably, roughly at my level as an amateur: it knows the rules, but its reasoning is superficial and it loses a game even against a weak machine opponent (GNU Chess at its lowest level.)

Tellingly, it is strong in the opening moves, when it can rely on its vast knowledge of the chess literature. It then becomes weak mid-game.

In my implementation, the model is asked to reason and then move. It comments as it reasons. When I showed the result to another instance of GPT-5, it made an important observation: language models have rhetorical competence, but little tactical competence.

This, actually, is a rather damning statement. It implies that efforts to turn language models into autonomous “reasoning agents” are likely misguided.

This should come as no surprise. Language models learn, well, they learn language. They have broad knowledge and can be extremely useful assistants at a wide variety of tasks, from business writing to code generation. But their knowledge is not grounded in experience. Just as they cannot track the state of a chess board, they cannot analyze the consequences of a chain of decisions. The models produce plausible narratives, but they are often hollow shells: there is no real understanding of the consequences of decisions.

This is well in line with recent accounts of LLMs failing at complex coordination or problem-solving tasks. The same LLM that writes a flawless subroutine under the expert guidance of a seasoned software engineer often produces subpar results in a “vibe coding” exercise when asked to deliver a turnkey solution.

My little exercise using chess offers a perfect microcosm. The top-of-the-line LLM, GPT-5, knows the rules of chess, “understands” chess. Its moves are legal. But it lacks the ability to analyze the outcome of its planned moves to any meaningful depth: thus, it pointlessly sacrifices its queen, loses pieces in reckless moves, and ultimately loses the game even against a lowest-level machine opponent. The model’s rhetorical strength is exemplary; its tactical abilities are effectively non-existent.

This reflects a simple fact: LLMs are designed to produce continuation of text. They are not designed to perform in-depth analysis of decisions and consequences.

The inevitable conclusion is that attempts to use LLMs as high-level agents, orchestrators of complex behavior without external grounding are bound to fail. Treating language models as autonomous agents is a mistake: they should serve as components of autonomous systems, but the autonomy itself must come from something other than a language model.

Neglecting to visit your fine blog for some time I sincerely remorse – it really provides good material to shake off dust from one’s brain :) Your experiments with GPT chess fascinated me from beginning, even to the degree that after experimenting a bit myself I wrote a quick article at local it-community site and got answer from some company which endeavors to build and sell “LLM-based solutions” and as a kind of marketing they tried to train some older GPT version specifically on a set of chess games. Trying their version I soon found it is as lousy as general-purpose models (with the same issues of not really knowing the rules and hence not being able to keep to them).

Now this note about GPT5 made a news for me, I read the phrase that “it knows rules” for that creators, probably, embedded some basic “chess-backend” to which it resides for help. But browsing internet I see that people say it still is not really strict on the rules.

I tried to play a few games, the first two or three it kept fairly well (at least until I had patience enough) – in one of them I was definitely impressed it overtricked my supposed trick (but I’m a hopeless player myself, supposedly “novice” by measure of chess.com or alike websites). However I tried in these games to vary opening moves. Surprisingly the most “silly” game was the one which started with one of the least ridiculous openings.

1. e4 d5

2. exd5 Qxd5

3. Nc3 Qa5

4. Nf3 Nf6

5. d4 Ne4

6. Bc4 Qxc3+

7. bxc3 Nxc3

8. Bxf7+ Kxf7

9. Ne5+ Ke8

10. Qf3

It’s perhaps “center-counter defence” or something like this. The second move for blacks is really childish though situation is not unique to this opening – queen shouldn’t take the pawn for it is forced away the next move and so “loses tempo” and has queen either returning or wandering over the board (which may be played well with much thought against weaker opponent probably but generally id discouraged). At move 6 when I was “cleverly” thinking of sacrificing my knight (at c3) instead rushing headlong to penetrate opponent’s king position – well, GPT opponent took the knight, but not with its own kinght as I thought – rather with queen (which is immediately lost). Thus I simply proceed with my plan of attacking f7 field, but having opponent weakened and almost completely undeveloped still.

What looks strange to me is that despite very long thinking it is even difficult to say whether it really plays openings better (as it supposedly should). Perhaps more games should be tried but with its current speed it is a bit tedious work.

For me example of the chess playing with GPT (which I learnt from you, thanks again) become the most “explanatory” argument when people ask about power of LLMs. It’s difficult and useless to explain people how it could make bugs in generated program code – as most people poorly understand the topic – but game of chess is well known and is something, seemingly, that most people understand much better even if they don’t play strong.

Another point I believe it is very “european-centric”, it could play chess to at least some moves – but most LLMs I tried are hopeless with chinese or japanese chess (xiang-qi and shogi) often simply not properly moving pieces at all (though saying “yes of course I can play” first).

Sorry for so verbose thoughts, but to conclude I’d suggest adding option of randomizing starting position (Fischer chess variant) to try playing without standard openings. This should be easy to add (especially with the help of gpt coding). Perhaps this may help in finding out how properly engine keeps to rules.

No, GPT has no chess back-end. It is a stochastic next-token predictor. That’s all it is. Very sophisticated, with a huge latent knowledge base thanks to its vast training corpus, but in the end, all it does is expanding text one token, one syllable at a time.

The reason why GPT is good at the start of a game is because its training corpus includes a lot of chess literature, so it knows about most openings. But once the possibilities explode mid-game, it loses competence, because a probabilistic next-token prediction in its answer is not the same as envisioning and planning moves.