Once again, I am playing with “low-end” language and multimodal AI running on my own hardware. And I am… somewhat astonished.

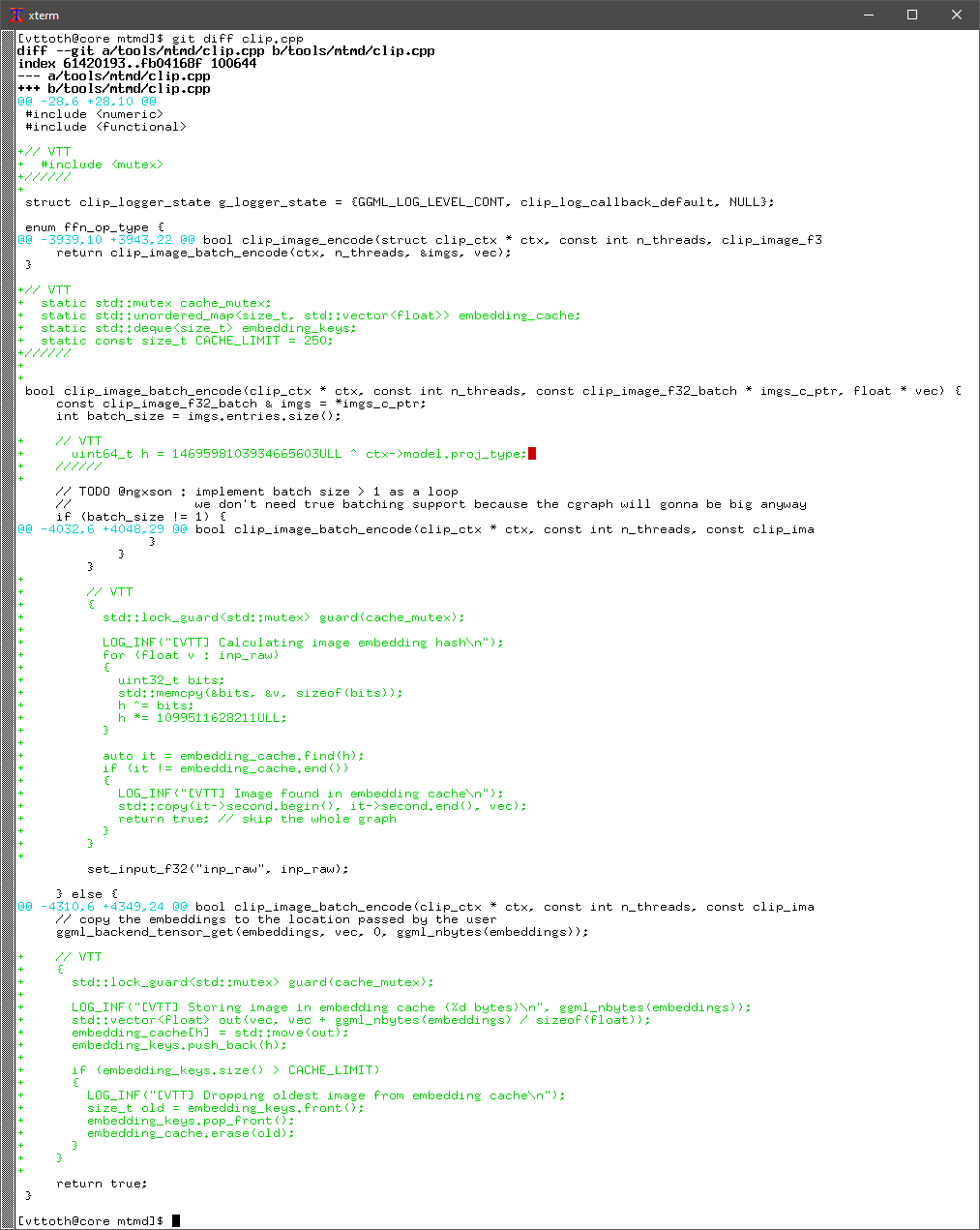

But first… recently, I learned how to make the most out of published models available through Hugging Face, using the Llama.cpp project. This project is a C++ “engine” that can run many different models if they are presented in a standard form. In fact, I experimented with Llama.cpp earlier, but only a prepackaged version. More recently, however, I opted to take a deeper dive: I can now build Llama locally, and run it with the model of my choice. And that is exactly what I have been doing.

How efficient is Llama.cpp? Well… we can read a lot about just how much power it takes to run powerful language models and the associated insane hardware requirements in the form of powerful GPUs with tons of high-speed RAM. Sure, that helps. But Llama.cpp can run a decent model in the ~10 billion parameter range even without a GPU, and still produce output at a rate of 3-5 tokens (maybe 2-3 words) per second.

But wait… 10 billion? That sounds like a lot until we consider that the leading-edge, “frontier class” models are supposedly in the trillion-parameter range. So surely, a “tiny” 10-billion parameter model is, at best, a toy?

Maybe not.

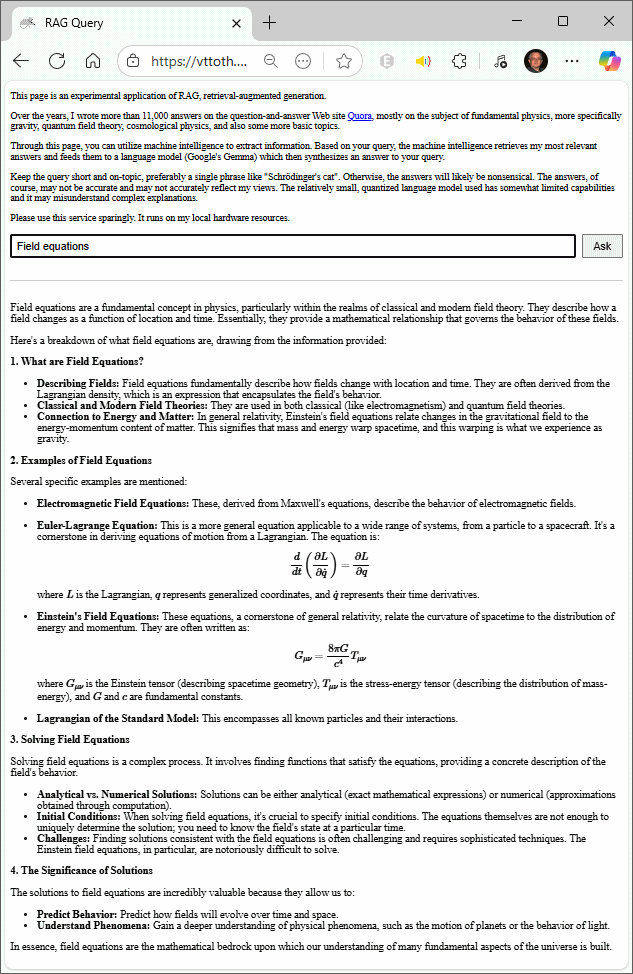

Take Gemma, now fully incorporated into my WISPL.COM site by way of Llama.cpp. Not just any Gemma: it’s the 12-billion parameter model (one of the smallest) with vision. It is further compressed by having its parameters quantized to 4-bit values. In other words, it’s basically as small as a useful model can be made. Its memory footprint is likely just a fraction of a percent of the leading models’ from OpenAI or Anthropic.

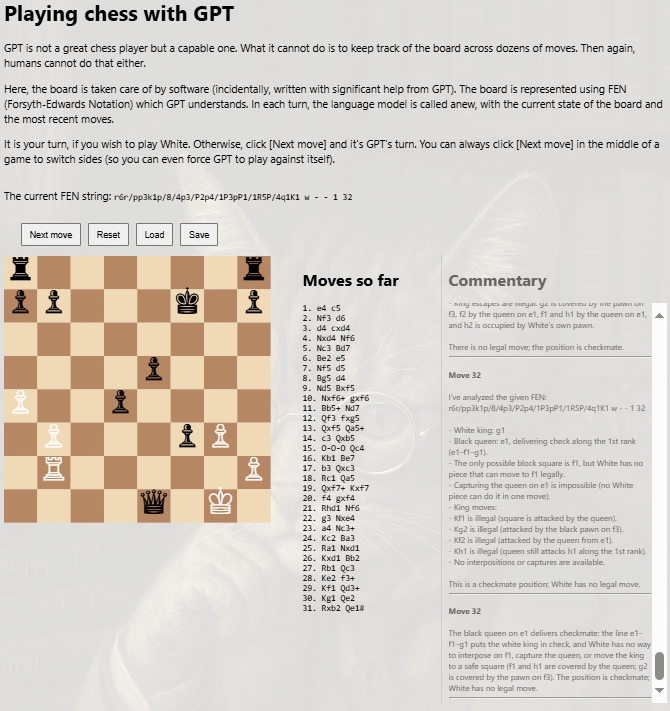

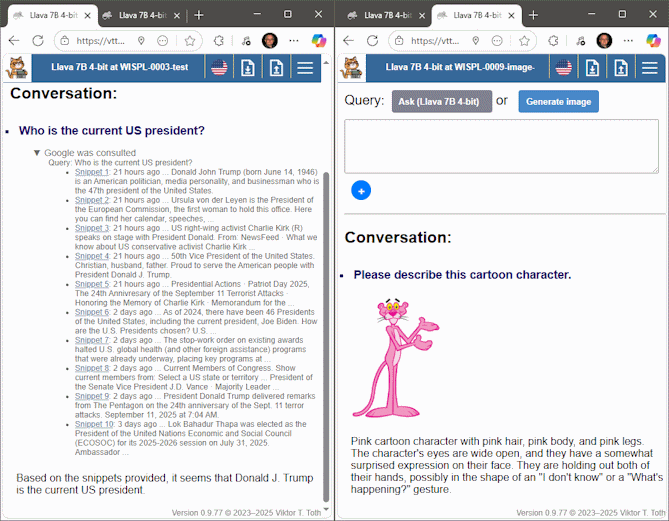

I had a test conversation with Gemma the other day, after ironing out details. Gemma is running here with a 32,768 token context window, using a slightly customized version of my standard system prompt. And look what it accomplished in the course of a single conversation:

- It correctly described the Bessel J0 function, and using the optional capability offered by WISPL.COM and described to it in its system prompt, it included a relevant plot.

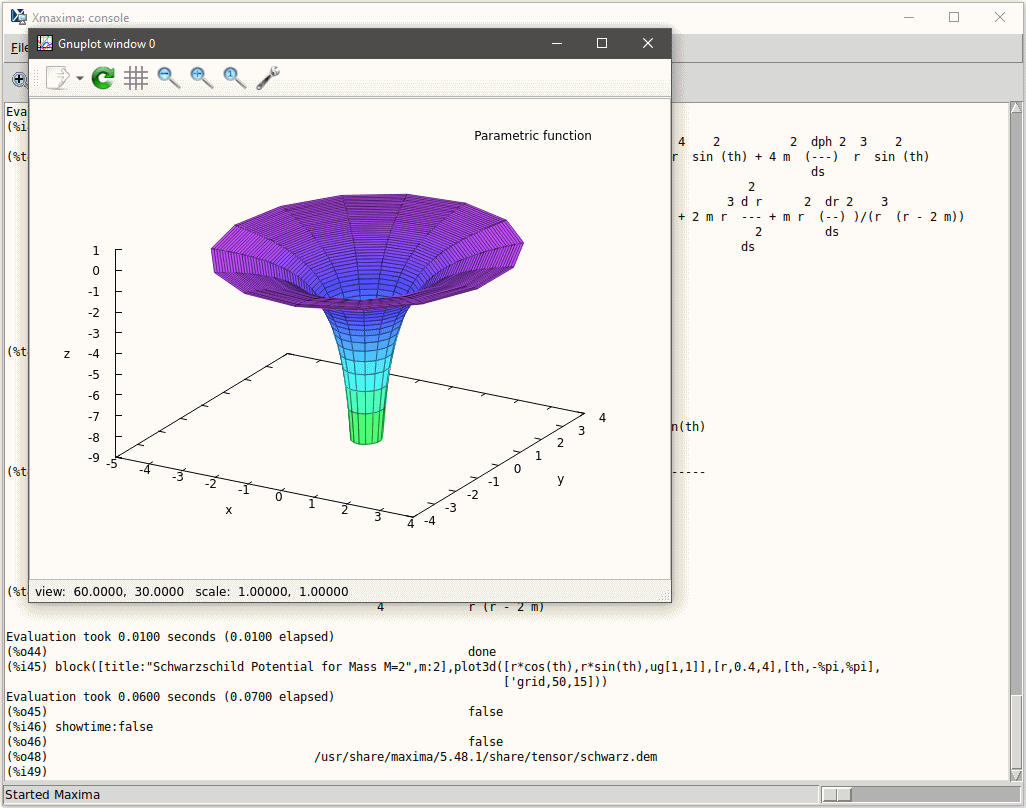

- Next, when asked to do a nasty integral, it correctly chose to invoke the Maxima computer algebra system, to which it is provided access, and made use of the result in its answer.

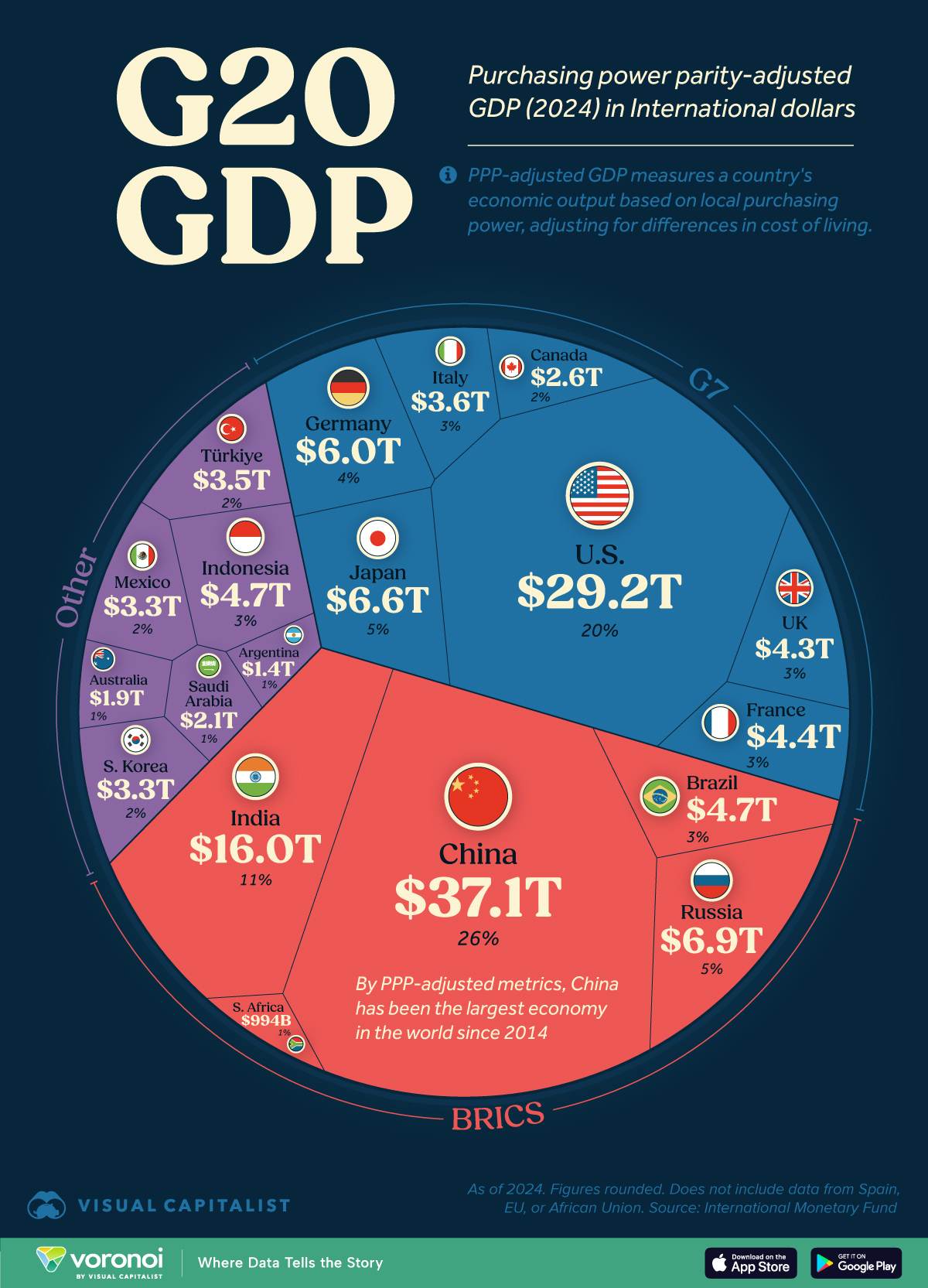

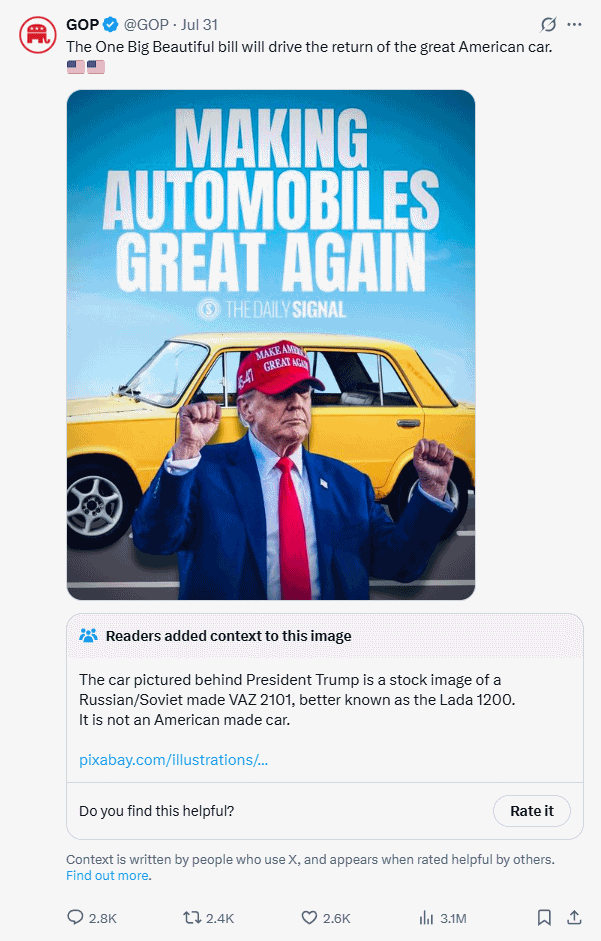

- Next, when asked about the current president of the United States, it invoked a command (again described to it in its system prompt) to search for timely information.

- Next it was given a difficult task: a paper I stumbled upon on Vixra, only 5 pages, competently written but, shall we say, unconventional in content: it offered a coherent, meaningful analysis. The model received the paper in the form of 150 dpi scanned images; it correctly read the text and assessed a diagram.

- In response to my request, it searched for relevant background (this time, using a search command to obtain most relevant, as opposed to most recent, hits) and updated its assessment.

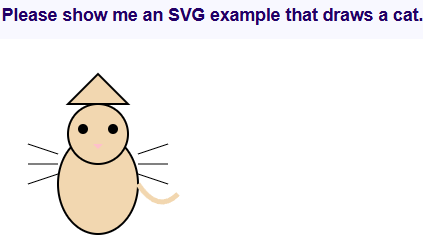

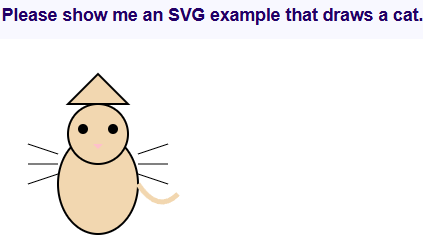

- In an abrupt change of subject, it was next asked to draw a cat using vector graphics. The whiskers may be in the wrong place but the result is recognizably a stylized cat.

- Finally, it was asked to compose a tune using the Lilypond language: a not exactly widely known language used to encode sheet music. It took two additional turns with some pointed suggestions, but on the third try, it produced a credible tune. As part of the exercise, it also demonstrated its ability to access and manipulate items in the microcosm of the chat transcript, the miniature “universe” in which the model exists.

Throughout it all, and despite the numerous context changes, the model never lost coherence. The final exchanges were rather slow in execution (approximately 20 minutes to parse all images and the entire transcript and generate a response) but the model remained functional.

prompt eval time = 1102654.82 ms / 7550 tokens ( 146.05 ms per token, 6.85 tokens per second)

eval time = 75257.86 ms / 274 tokens ( 274.66 ms per token, 3.64 tokens per second)

total time = 1177912.68 ms / 7824 tokens

This is very respectable performance for a CPU-only run of a 12-billion parameter model with vision. But I mainly remain astonished by the model’s capabilities: its instruction-following ability, its coherence, its robust knowledge that remained free of serious hallucinations or confabulations despite the 4-bit quantization.

In other words, this model may be small but it is not a toy. And the ability to run such capable models locally, without cloud resources (and without the associated leakage of information) opens serious new horizons for diverse applications.