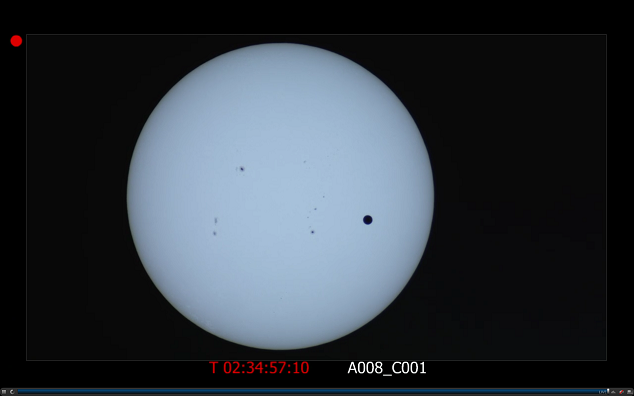

Yesterday, Venus transited the Sun. It won’t happen again for more than a century.

I had paper “welder’s glasses” courtesy of Sky News. Looking through them, I did indeed see a tiny black speck on the disk of the Sun. However, it was nowhere as impressive as the pictures taken through professional telescopes.

These live pictures were streamed to us courtesy of NASA. One planned broadcast from Alice Springs, Australia, was briefly interrupted. At first, it was thought that a road worker cutting an optical cable was the culprit, but later it turned out to be a case of misconfigured hardware. Or could it be that they were trying to fix a problem with an “intellectual property address”, a wording that appeared on several Australian news sites today? (Note to editors: if you don’t understand the text, don’t be over-eager replacing acronyms with what you think they stand for.)

I also tried to take pictures myself, holding my set of paper welder’s glasses in front of my (decidedly non-professional) cameras. Surprisingly, it was with my cell phone that I was able to take the best picture, but it did not even come close in resolution to what would have been required to see Venus.

The lesson? I think I’ll leave astrophotography to the professionals. Or, at least, to expert amateurs. Unfortunately, I am neither.

That said, I remain utterly fascinated by the experience of staring at a sphere of gas, close to a million and a half kilometers wide, containing 2 nonillion (2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) kilograms of mostly hydrogen gas, burning roughly 580 billion kilograms of it every second in the form of nuclear fusion deep in its core, releasing photons amounting to about 4.3 billion kilograms of energy… and most of these photons remain trapped for a very long time, producing extreme pressures (so that the interior of the Sun is dominated by this ultrarelativistic photon gas) that prevent the Sun from collapsing upon itself, which will indeed be its fate when it can no longer sustain hydrogen fusion in its core a few billion years from now. And then, this huge orb is briefly occulted by a tiny black speck, the shadow of a world as big as our own… just a tiny black dot, too small for my handheld cameras to see.

I sometimes try to use a human-scale analogy when trying to explain to friends just how mind-bogglingly big the solar system is. Imagine a beach ball that is a meter wide. Now suppose you stand about a hundred meters away from it, like the length of a large sports field. Okay… now imagine that that beach ball is so bleeping hot, even at this distance its heat is burning your face. That’s how hot the Sun is.

Now hold up a large pea, about a centimeter in size. That’s the Earth. Another pea, roughly halfway between you and the beach ball would be Venus.

A peppercorn, some thirty centimeters or so from your Earth pea… that’s the Moon. Incidentally, if you hold that peppercorn up, at about thirty centimeters from your eye it is just large enough to obscure the beach ball in the distance, producing a solar eclipse.

Now let’s go a little further. Some half a kilometer from the beach ball you see a large-ish orange… Jupiter. Twice as far, you see a smaller orange with a ribbon around it; that’s Saturn. Pluto would be another peppercorn, more than three kilometers away.

But your beach ball’s influence does not end there. There will be specks of dust in orbit around it as far out as several hundred kilometers, maybe more. So where would the next beach ball be, representing the nearest star? Well, here’s the problem… the surface of the Earth is just not large enough, because the next beach ball would be more than 20,000 kilometers away.

To represent other stars, not to mention the whole of the Milky Way, we would once again need astronomical distance scales. If a star like our Sun was a one meter wide beach ball, the Milky Way of beech balls would be larger than the orbit of the Earth around the Sun. And the nearest full-size galaxy, Andromeda, would need to be located in distant parts of the solar system, far beyond the orbits of planets.

The only way we could reduce galaxies and groups of galaxies to a scale that humans can comprehend is by making stars and planets microscopic. So whereas the size of the solar system can perhaps be grasped by my beach ball and pea analogy, it is simply impossible to imagine simultaneously just how large the Milky Way is, not to mention the entire visible universe.

Or, as Douglas Adams wrote in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “Space is big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space.”