Now that Roy Kerr’s paper on black holes and singularities is on arXiv, I am sure I’ll be asked about it again, just as I have been asked about it already on Quora.

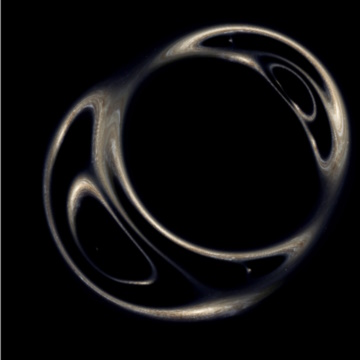

Roy Kerr, of course, is one of the living legends of relativity theory. His axisymmetric solution, published in the year of my birth, was the first new solution in nearly half a century after Karl Schwarzschild published his famous solution for a spherically symmetric, static, vacuum spacetime. I hesitate to be critical of this manuscript since chances are that Kerr is right and I am wrong.

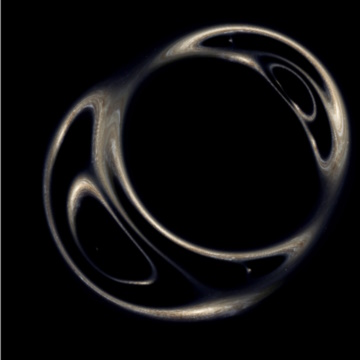

Kerr now argues that the singularity theorems are nonsense, and that his axisymmetric solution actually hides some nonsingular configuration of matter therein.

At a first glance, the paper seems well written and robust. Still… when I dug into it, there are a few things that caught my attention, and not in a right way. First, the paper takes argument with “singularity believers” using language that almost sounds like pseudoscience. Second, it has some weird factual errors. E.g., it asserts that black holes “as large as 100 billion solar masses have been observed by the James Webb Telescope” (not even close). Or, it describes the famous Oppenheimer-Snyder paper of 1939 as having “used linear, nineteenth century ideas on how matter behaves under extreme pressures” (actually, Oppenheimer and Snyder discuss the collapse of a “dust” solution with negligible pressure using the tools of general relativity with rigor). Kerr further criticizes the Oppenheimer-Snyder paper as attempting “to ‘prove’ that the ensuing metric is still singular”, even though that paper says nothing about the metric’s singularity, only that the collapsing star will eventually reach its “gravitational radius” (i.e., the Schwarzschild radius). Nonetheless, later Kerr doubles down by writing that “Oppenheimer and Snyder proved that the metric collapses to a point,” whereas the closest the actual Oppenheimer-Snyder paper comes to this is describing collapsing stars as stars “which cannot end in a stable stationary state”.

Never mind, let’s ignore these issues as they may not be relevant to Kerr’s argument after all. His main argument is basically that Penrose and Hawking deduced the necessary presence of singularities from the existence of light rays of finite affine length; i.e., light rays that, in some sense, terminate (presumably at the singularity). Kerr says that no, the ring singularity inside a Kerr black hole, for instance, may just be an idealized substitute for a rotating neutron star.

Now Kerr has an interesting point here. Take the Schwarzschild metric. It is a vacuum solution of general relativity, but it also accurately describes the gravitational field outside any static, spherically symmetric distribution of matter in the vacuum. So a Schwarzschild solution does not imply an event horizon or a singularity: they can be replaced by an extended, gravitating body that has no singularities whatsoever so long as the radius of the body is greater than the Schwarzschild radius associated with its mass. The gravitational field of the Earth is also well described by Schwarzschild outside the Earth. So in my reading, the crucial question Kerr raises is this: Is it possible that once we introduce matter inside the event horizon of a Kerr black hole, perhaps that can eliminate the interior Cauchy horizon or, at the very least, the ring singularity that it hides?

I don’t think that is the case, and here is why. Between the two horizons of a Kerr black hole, the “radial” coordinate is now the timelike coordinate, with the future pointing “inward”, i.e., towards the Cauchy horizon. That means that particles of matter do not have trajectories that would allow them to avoid the Cauchy horizon; no matter what path they follow, they will reach that horizon in finite proper time.

Inside the Cauchy horizon, anything goes, since closed timelike curves exist. So presumably, it might even be possible for particles of matter to travel back and forth between the past and the future, never hitting the ring singularity. But that’s not what Kerr is suggesting in his paper; he’s not talking about acausal worldlines inside the Cauchy horizon, but some “nonsingular interior star”. I don’t see how to make sense of that suggestion, because I don’t see how a stationary configuration of matter could exist inside the inner horizon. Wobbling back-and-forth between yesterday and tomorrow in a closed timelike loop is not a stationary configuration!

For these reasons, even as I am painfully aware that I am arguing with a Roy Kerr so there’s a darn good chance that he’s right and I’m spouting nonsense, I must say that I remain unconvinced by his paper. The language he uses (e.g., describing the business of singularities as “dogma”) is not helping either. Also, his description of the interior of the rotating black hole sounds a bit off; to use his own words, “nineteenth century” reasoning, much more so than the Oppenheimer-Snyder paper that he criticizes.